This chapter is part of my dissertation. The full thesis is available online as a PDF or can be read chapter by chapter on this website.

Basics of cardiac electrophysiology

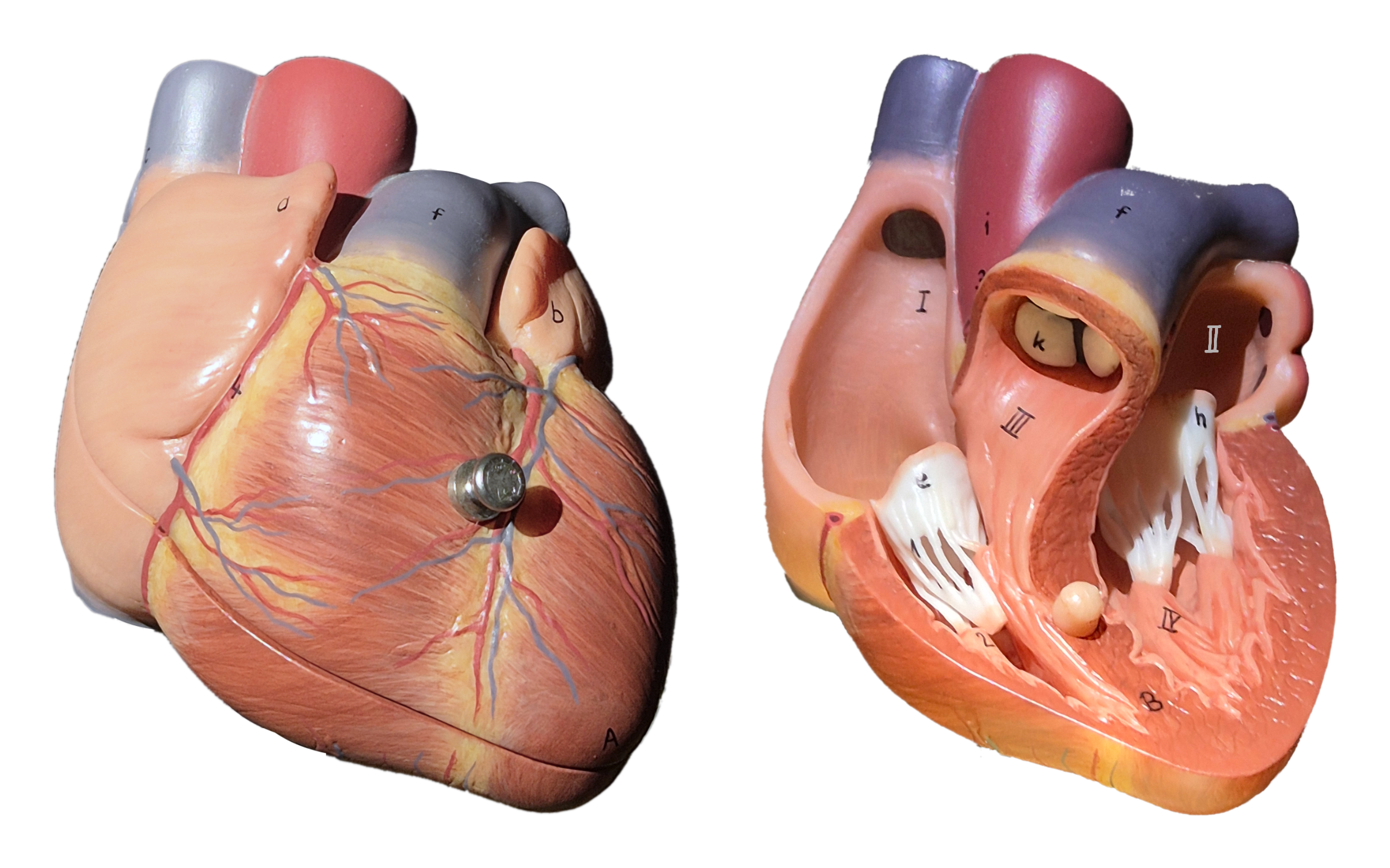

The vital mechanical contraction of the heart is driven by electrical waves that travel through the heart muscle tissue—the myocardium. In sinus rhythm—the normal heart rhythm—the heart activates in a well-choreographed sequence to pump blood effectively to the organs: The sinoatrial node in the right atrium acts as the pacemaker of the heart emitting an electrical pulse. The pulse then travels to the left atrium via Bachmann’s bundle, such that both atria contract at the same time. After the pulse reaches the atrioventricular node, it travels through the bundle of His and the Purkinje fibres to and through the ventricular wall, causing the ventricles to contract after the atria (Schiebler, 2005; Zipes & Jalife, 2014). Photographs of an anatomical model of the human heart can be found in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Anterior view of the human heart in an anatomical model. The organ has four chambers: the smaller right (I) and left atria (II) superior of the larger right (III) and left ventricles (IV). Electrical waves coordinate its contraction pumping blood to the organs. Blood-flow is regulated by the opening and closing of valves between the chambers.

Arrhythmias are deviations from this normal heart rhythm. An abnormally low heart rate is called bradycardia1, while an abnormally high heart rate is called tachycardia2. Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is associated with a high risk of sudden cardiac death and is caused by re-entrant circuits in the ventricles, i.e., electrical waves that circulate in the ventricles repeatedly exciting them too early. It can evolve into ventricular fibrillation (VF), which is chaotic electrical activity in the ventricles leading to severely reduced pumping capacity of the heart and sudden cardiac death if not treated immediately with a defibrillator. Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia and is not immediately life-threatening, but it can lead to stroke and heart failure if not treated properly (Zipes & Jalife, 2014).

The field of cardiac electrophysiology studies how electrical waves propagate through the heart and how they cause arrhythmias. It is a field that operates on a variety of different levels: from the patient, to the organ, tissue, cell, and subcellular level. The field is highly interdisciplinary, combining knowledge from medicine, biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, computer science, and engineering. The goal is to not just understand and diagnose the electrical activation patterns, but also to control them to ensure the proper working of each patient’s heart.

In recent years, efforts have been made to create personalised computational models of the heart, so-called cardiac digital twins, which could be used to test and optimise treatment strategies for individual patients (Bhagirath et al., 2024; Costabal et al., 2020; Gillette et al., 2021; Koopsen et al., 2024; Martin et al., 2022; Niederer et al., 2019; Shahi et al., 2022; Trayanova et al., 2020). Machine learning based approaches, for instance, utilising the data from wearable sensors (Chen et al., 2025) and other biomedical applications such as optoelectronics for cardioversion (Portero et al., 2024) show promise to impove the diagnosis and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias and their causes in the coming years. I have contributed to the concept of cardiac digital twins in a variety of ways through scientific articles, some of which are included in this dissertation:

- the development of numerical software to simulate the electrical activity of the heart, see chapter 2 (Kabus, Cloet, et al., 2024),

- the detection of re-entrant circuits in the heart as phase defects, see chapter 3 (Kabus et al., 2022),

- the description of arrhythmia formation via quasiparticles in Feynman-like diagrams, see chapter 4 (Arno et al., 2024a), and

- the creation of data-driven models for cardiac electrophysiology directly from optical voltage mapping data, see chapter 5 (Kabus, De Coster, et al., 2024).

The remainder of this chapter provides background knowledge that is helpful to understand the work presented in the published articles. It begins with a brief overview of cardiac action potentials and central quantities used to describe them. We then discuss the cell cultures and experiments that were conducted to obtain the data used for the creation of the computational models, and how these data are processed. Next, an overview of conventional in-silico models of cardiac electrophysiology is given, followed by an introduction into phase mapping. The introductory chapter concludes with the basics of machine learning on which the data-driven models are based.

Propagation of action potential waves

Excitation waves propagate by neighbouring cells activating each other. Each heart muscle cell—cardiac myocyte—activates and deactivates in a repeating cycle: the action potential. The activation, also known as depolarisation, is much quicker than the deactivation, the repolarisation. The cell’s transmembrane voltage $u$—in units of —is the difference in electrical potential between the inside and the outside of the cell; it is one of the central quantities in the field of cardiac electrophysiology. During the action potential of a single cell, the transmembrane voltage first increases from a resting potential of about to a peak of about exact values vary between cell types. This is called the upstroke of the action potential. After the peak, the voltage remains roughly constant for to the plateau phase, before it decreases back to the resting voltage (Zipes & Jalife, 2014).

We call the time at which $u$ rises above a threshold, the local activation time (LAT); and when it falls below threshold, the local deactivation time (LDT). The time between a cell’s activation and deactivation is called the action potential duration (APD): $$ \text{APD} = \text{LDT} - \text{LAT} \qquad{(1)}$$ Analogously, we call the time between deactivation and activation the diastolic interval (DI): $$ \text{DI} = \text{LAT} - \text{LDT} \qquad{(2)}$$ The cycle length (CL) is the time between two subsequent activations of a cell: $$ \text{CL} = \text{LAT}_2 - \text{LAT}_1 \qquad{(3)}$$ Note that these quantities depend on the chosen threshold. For example, when measured at of the upstroke, the APD is more precisely referred to as APD30 .

Another central quantity is the conduction velocity (CV), which is the speed at which the excitation wave travels through the tissue. It is usually measured as the average speed of the sharp wave front between two points in space: $$ \text{CV} = \frac{\Delta x}{\Delta t} \qquad{(4)}$$ where $\Delta x$ is the distance between the two points and $\Delta t$ is the time it takes for the wave front to travel this distance. This definition is prone to errors when the points are not well-aligned with the direction of wave propagation. Also, as it is averaged, it does not capture local variations in CV. More rigorous definitions exist, for instance, by taking the infinitesimal limit of the above equation and the length of the velocity vector ${{\bm{{v}}}} \in \mathbb R^{D}$, where $D$ is the number of spatial dimensions: $$ \text{CV} = {{\left\lVert {{\bm{{v}}}} \right\rVert}} \qquad{(5)}$$

In Fig. 2, typical action potentials of an atrial model are shown for four pulses in a cable simulation as functions of space and time. In the space-time plot in panel C, the CV is measured as the slope of the wave front. Depending on the timing of the pulses, the APD and CV varies. The fourth pulse is blocked, i.e., it does not propagate through the cable.

Figure 2: Atrial action potentials in a cable simulation. These data were obtained using a numerical simulation of the model by Courtemanche et al. (1998), as will be introduced in section 2.3. A. Subsequent action potentials have different APD30 depending on the previous DI, i.e., timing. B. The excitation wave travels through the cable. C. In a space-time plot of the activation pattern, the CV can be measured as the slope $\Delta x / \Delta t$ of the wave front. In this view, it can also easily be seen that the fourth pulse is blocked.

APD and CV depend on the so-called restitution characteristics which vary between different cell types. Restitution curves are plots of APD or CV against the DI or CL, an example of these curves is shown in Fig. 5.7.

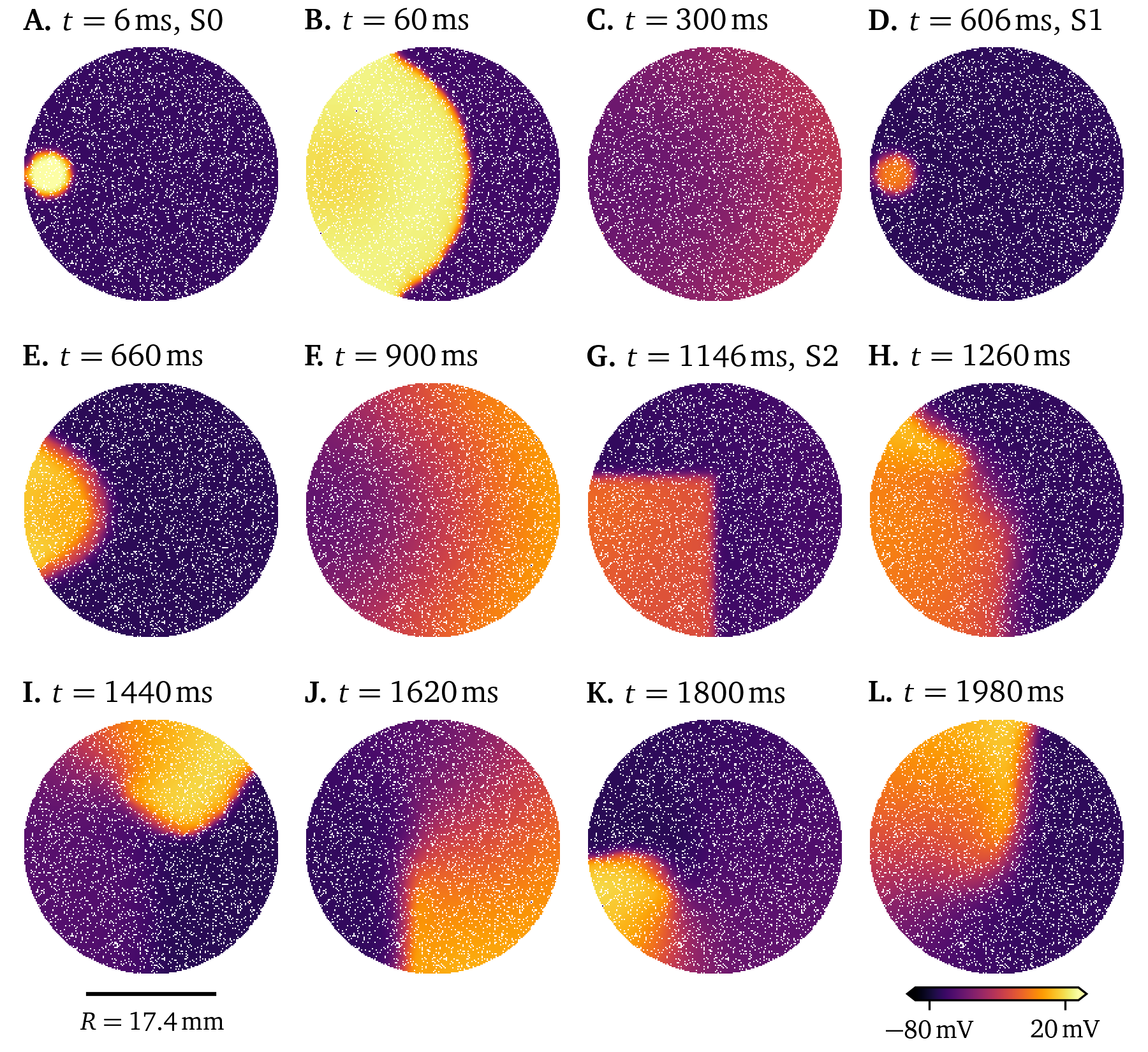

As it has such a big impact on the action potential, the timing of the stimuli is another important aspect of cardiac electrophysiology. The so-called stimulus protocol is the sequence of the timings and locations of the stimuli, usually applied using an electrode. Common protocols are S1S2 where the tissue is re-excited just behind a part of the wave back of a first wave, or burst pacing where several stimuli are applied at the same location in quick succession. Due to inhomogeneities in the tissue, this might lead to re-entry—repeated excitation, which will be discussed below. In stochastic burst pacing (SBP), stimuli at the same electrode location are applied at random intervals to record the response of the tissue to a large variety of timings to get a more complete picture of the cells’ behaviour in unusual settings (Kabus, De Coster, et al., 2024).

A model cell line of human atrial myocytes

To study the electrical properties of cardiomyocytes, it is common to use model cells that can be relatively easily obtained, cultured, and manipulated in the laboratory. There is a wide variety of cells in use, for example neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) (Majumder et al., 2016), or pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (PSC-CMs) (Karakikes et al., 2015).

At Leiden University Medical Center, a new cell line was recently developed that was derived from human fetal atrial tissue which was conditionally immortalised using a lentiviral vector-based system. These so-called human immortalised atrial myocytes (hiAMs) are more representative of human atrial myocytes than other cells enabling their use in a wide range of experiments with cells (Harlaar et al., 2022):

hiAMs are monoclonal, meaning that they are derived from a single cell and are hence genetically identical. This leads to a high consistency in phenotypic properties of the cells, such as their CV and APD. They also posses superior electrophysiological properties compered to human embryonic stem cell-derived atrial myocytes (hESC-AMs) or human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived atrial myocytes (hiPSC-AMs). Observed CVs of hiAMs are around with APD80 of compared to at similar APDs for hESC-AMs (Harlaar et al., 2022).

hiAMs can be expanded almost indefinitely as de-differentiated cells in the presence of the inducing agent doxycycline, and upon its removal, they re-differentiate into functional cardiomyocytes. This allows for the creation of large quantities of cells for experiments, such as the creation of monolayers—one-cell-thick layers grown on a flat surface. As the cells are randomly oriented in the monolayer, the resulting two-dimensional and approximately homogeneous and isotropic tissue can be used to study action potential propagation and re-entry in a controlled way. One use of these monolayers is to study the effects of pro- or anti-arrhythmic drugs on the electrical properties (Harlaar et al., 2022).

A visual outline of the creation of hiAMs is given in figure 1 of the article introducing the cell line (Harlaar et al., 2022): After the cells are isolated from a human fetus, they are transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding the recombinant simian virus 40 large T (SV40LT) antigen under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter. The effect of SV40LT on the cells is that they continuously divide. Cell clones are filtered based on selection criteria, such as the ability to proliferate in a doxycycline-dependant manner and to undergo cardiomyogenic differentiation into excitable and contractile cells. The selected cells now have the ability to proliferate in the presence of doxycycline and to differentiate into functional atrial myocytes upon its removal, i.e., without SV40LT expression (Harlaar et al., 2022).

The hiAM cell lines are a promising new tool for studying the electrical properties of the human atria. In chapter 5, optical voltage mapping of focal waves in hiAM monolayers was used as an in-vitro data set to train a data-driven in-silico model. The spiral waves predicted by that model were compared to spiral waves in hiAM monolayers (Kabus, De Coster, et al., 2024). In the following section, we will present some experiments that are commonly performed to measure the electrophysiological activity of cardiomyocytes, such as patch-clamping and optical mapping, which are relevant for the work in this project.

Common experiments in cardiac electrophysiology

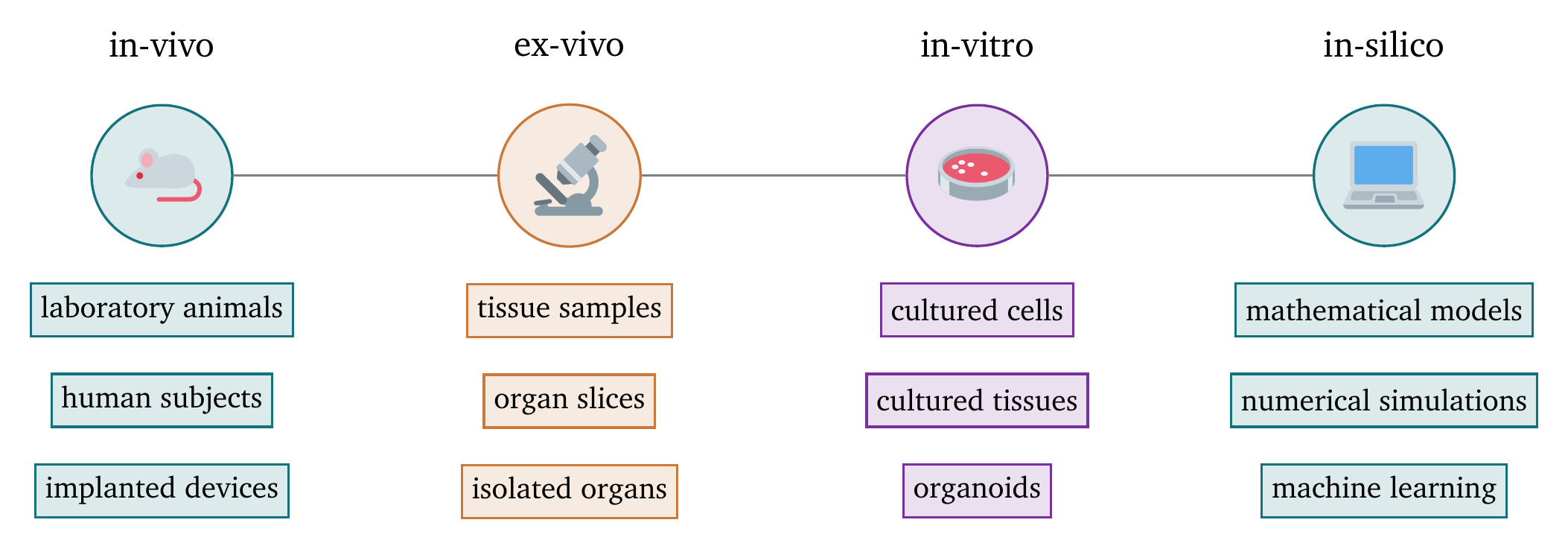

Experiments in the discipline of medicine are often graded on a scale from most-invasive to least-invasive as follows, see also Fig. 3:

- In-vivo experiments are performed on living organisms, usually laboratory animals. This is the most realistic setting, but also the most invasive, expensive, and ethically challenging.

- Ex-vivo experiments are performed on tissue samples or organs extracted from organisms that is artificially kept alive outside of the animal. This still requires animal sacrifice.

- In-vitro experiments are performed “in the glass”—i.e., on isolated cells or tissues that are kept alive in a culture dish. Cell lines are cultured to study the behaviour of (populations of) individual cells.

- In-silico experiments are performed on computers. The term refers to the use of silicon in computer chips. This is naturally the least invasive method, but also the most abstract. In-silico models must be created using in-vivo, ex-vivo, or in-vitro data and validated against them.

Figure 3: Scale of the invasiveness of medical experiments. The scale ranges from most invasive on the left to least invasive on the right.

In this dissertation, we focus on in-silico experiments motivated by in-vivo, ex-vivo, and in-vitro experiments. In the following sections, we will briefly introduce the types of experiments that are the most relevant for the research presented in this dissertation.

Measurement of single-cell behaviour using patch clamping

Patch clamping is an in-vitro or ex-vivo technique to measure the electrical activity of a single cell. Under a microscope, a glass pipette is carefully attached to the cell membrane. Depending on the quantity that should be measured, the pipette can either leave the cell membrane intact, for instance, to measure the activity of individual ion channels, or penetrate the cell membrane to measure the activity of the entire cell. As the pipette is filled with a solution that conducts electricity, the electrical response of the cell to an applied voltage can be measured (Hill & Stephens, 2021).

Patch clamping was used to measure electrical properties of hiAMs, such as various ionic currents to compare their electrophysiology with that of other cell types. As these cells are an in-vitro model of human atrial myocytes, they should behave similarly to the cells they aim to model. Patch-clamping was therefore mainly used as a tool to validate the hiAMs as a new in-vitro model in the original publication introducing them by Harlaar et al. (2022). This validation justifies the use of hiAMs for future electrophysiological experiments.

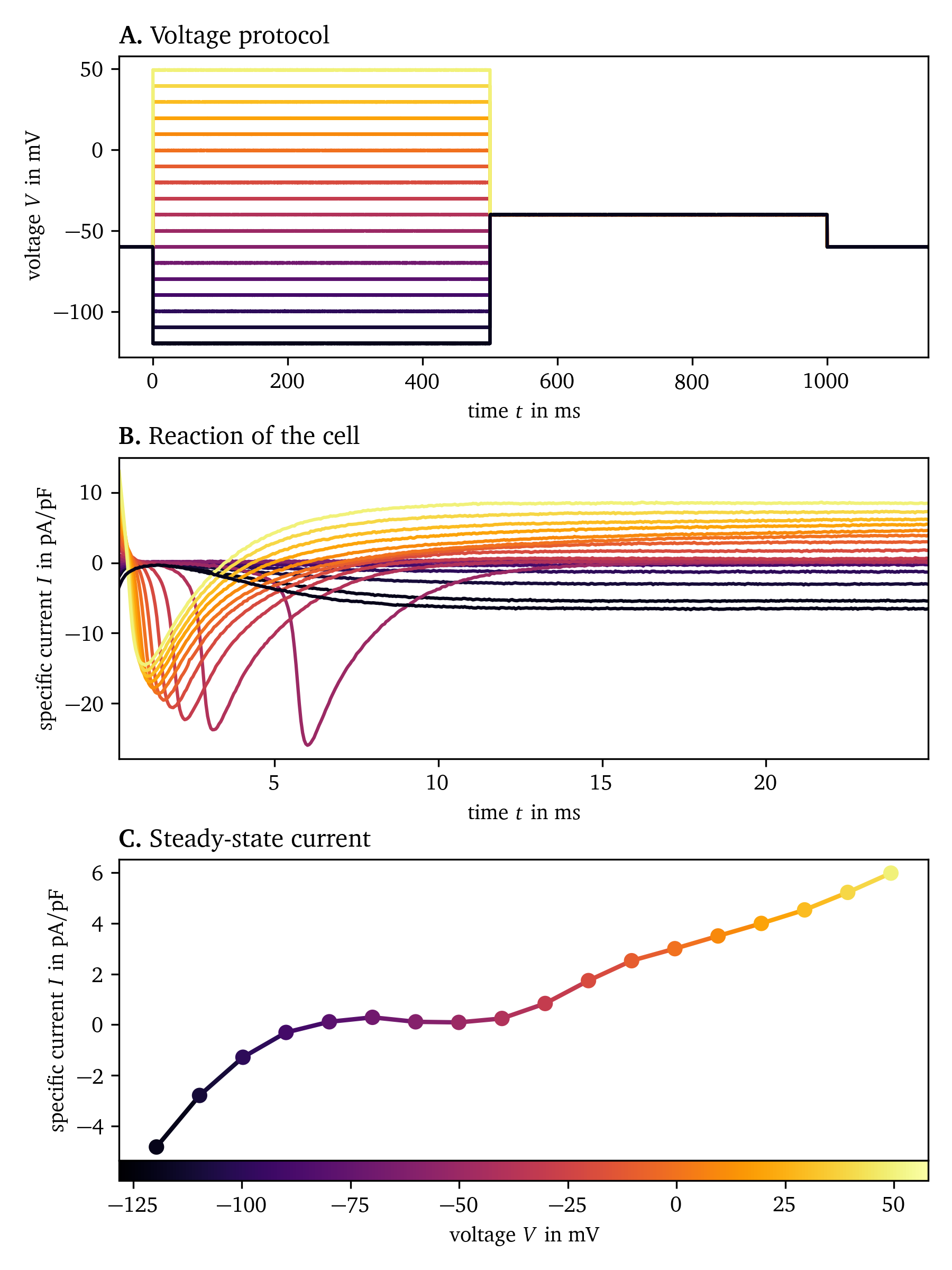

Fig. 4 shows how the steady-state current is obtained for a hiAM. A voltage step protocol is applied to stimulate the cell, and the current over time is measured. After an initial transient phase, the current stabilises to the steady-state current. The result of this experiment is a current-voltage curve describing the specific current across the membrane as a function of the applied voltage.

Figure 4: Measurement of the steady-state current of hiAMs using patch clamping. A. The voltage is varied in steps from to and held for . B. The specific current across the membrane is measured for each voltage step. C. Steady-state current as a function of voltage. Experimental data from Harlaar et al. (2022), recorded at Amsterdam Medical Center.

Since the publication of Harlaar et al. (2022), additional patch-clamp experiments have been performed to measure a greater variety of ionic currents in hiAMs. These data are currently being analysed and will be published in a follow-up paper which will introduce a new in-silico electrophysiological model of hiAMs (De Coster et al., in preparation). The in-silico model will follow the classical approach to design a mathematical model of the cells’ electrophysiology to work in the context of the bi- and monodomain description which will be introduced in section 2.

Mapping techniques for tissue-level electrical excitation waves

To study the propagation of excitation waves in cardiac tissue, its electrical activity must be recorded simultaneously at multiple locations. As the electrical activity over space is recorded, this is called mapping. While the transmembrane voltage can not easily be measured directly for mapping, we instead measure by proxy.

On the one hand, electrodes can be used to record the electrical potential in so-called electrograms (EGMs) at different locations, see also section 2.1. The electrodes may be placed on the surface of the tissue or inserted into the tissue. This can be done in-vitro, ex-vivo, or even in-vivo. The electrodes are often arranged in a grid or linear patterns. Catheters with multiple electrodes can be inserted into the heart, such as the PentaRay catheter by Biosense Webster with a 5-star-shaped array of 20 electrodes or the HD Grid catheter by Abbott with a 4x4 grid of electrodes (Berte et al., 2020). Recordings from multiple beats can be combined to create phase maps of recurring patterns of activation, see also section 3.

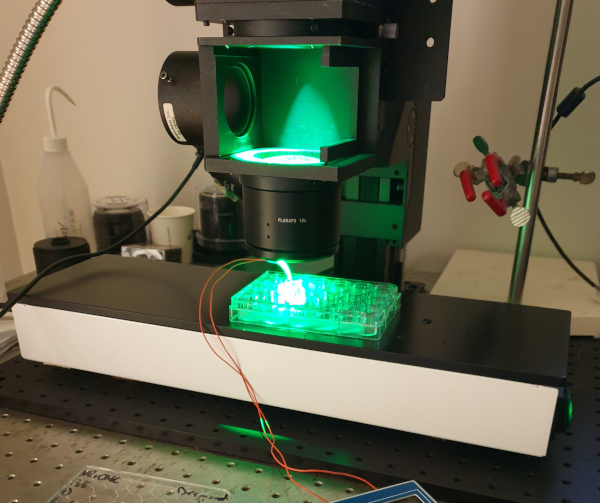

On the other hand, optical mapping techniques usually record the fluorescence of voltage- or Ca2+ -sensitive dyes (Entcheva & Kay, 2021). A commonly used potentiometric dye is di-4-ANEPPS, which, when it absorbs light in blue to green wavelengths, emits red light whose intensity changes in a way that is approximately proportional to the transmembrane potential (Loew, 1996).

The setup for optical mapping typically consists of the following components: A light source, such as a halogen lamp, whose light may need to be filtered to the desired wavelengths. A dichroic mirror reflects the excitation light to the sample, while allowing the emission light to pass through. An emission filter also blocks the excitation light and only allows the desired, emitted wavelengths to pass through to the camera. The camera and a stimulation mechanism such as an electrode are controlled by a computer. A photograph of a simple optical mapping setup is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Optical mapping setup with a camera out of frame at the top, green light from the top, lenses for focusing and magnification, and the sample—a 24-well plate. As a simple mechanism for stimulating the tissue, a bipolar electrode is placed in the well. The camera and electrodes are controlled by a computer. To keep the tissue at body temperature, the sample is placed on a heating plate.

Both high temporal and spatial resolution are required for optically mapping the electrical activity of cardiac tissue, fast enough to capture the rapid changes over time and fine enough to capture the details of wave propagation through the tissue. The amount of noise is higher at higher resolutions due to less photons being collected per pixel and frame. Frame rates used for the data collected in this work are in the range of 1 to per frame. The spatial resolution is typically around 150 to per pixel, depending on the choice of lenses and camera. For example, the MiCAM05-Ultima camera by SciMedia has a resolution of 100x100 pixels onto which the imaging plane is projected (Harlaar et al., 2022).

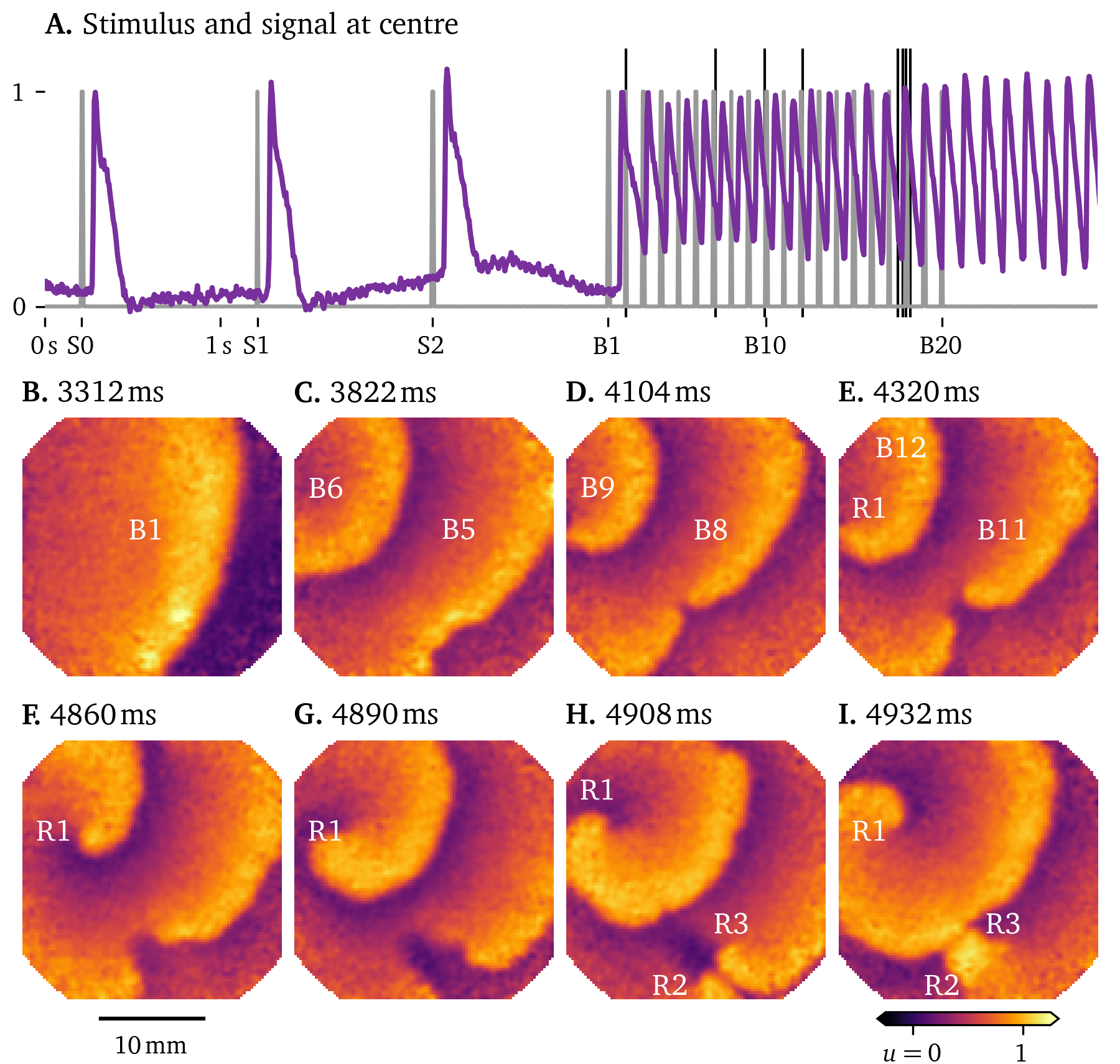

As an example of the data that can be recorded with optical mapping, we show in Fig. 6 a sequence of snapshots of the electrical activity in a hiAM monolayer in a 6-well dish. This experiment shows the formation of a figure-of-eight spiral wave under burst pacing. During subsequent pulses, the gap of blocked conduction between the two sides of a wave front builds up to the point where there is enough space for the front to turn in on itself, creating a pair of spirals.

Figure 6: Figure-of-eight spiral formation under burst pacing in hiAM monolayers in a 6-well dish. A. The stimulation protocol in gray consists of three pulses at labelled S1-3, followed by a burst of 20 pulses at , B1-20. These stimuli trigger focal waves emanating from the electrode at the top left in the frame. The response of the central pixel is shown in purple. B.-I. Snapshots of the activity at the times indicated by the thin black lines in A. Frames are chosen at times when an excitation wave crosses a region of interest to show the build-up to figure-of-eight spiral wave formation from pulse to pulse. E. At the top left, a spiral wave forms in sync with the pacing, labelled R1. F.-I. The gap between the two parts of the wave front is so wide, that in the next frames, the wave front can turn around and merge with the next wave front, forming a figure-of-eight spiral wave. H. The two spirals in the figure-of-eight spiral wave are labelled R2 and R3.

In contrast to single cell measurements, optical mapping can capture the complex patterns of excitation waves in tissue. The data are particularly rich as each pixel may have a different time series of excitation and average cell properties, providing a large variability in the data. This variability can be used in the development of data-driven methods to model the electrical activity of cardiac tissue, a main focus of this work.

Processing and analysis of mapping data

Especially at higher resolutions, optical mapping recordings can be so noisy and obscured by other artefacts making it difficult to extract useful information from them. To focus on the relevant parts of the data, there are a variety of processing steps that can be applied. It is important to balance the removal of noise with preservation of the signal without distortion.

One of the most used steps in data processing is smoothing which gets its name from making noisy, jagged data smoother. This is typically done by applying an averaging filter to the data: The smoothed value at a given point is the average of the values of the data points in a small neighbourhood around it. A larger neighbourhood will result in smoother data, but the signal will be less clear, i.e., blurred. If the neighbourhood is too small, the noise will not be removed effectively. Smoothing and blurring are, mathematically speaking, the same operation, which is described by the diffusion equation, also known as the heat equation (Eq. 27). Smoothing can also be done in the frequency domain by applying a low-pass filter, for instance via the Fourier transform. Optical mapping data can be smoothed in time and the two spatial dimensions, note however that smoothing in time violates the causality of the data, meaning that the smoothed data at a given time point will depend on future data points.

A way to smoothen data without violating causality is to use an exponential moving average (EMA). The EMA is a recursive filter that gives more weight to recent data points. The EMA of a time series $u(t)$ at time $t$ is defined as (Heckert et al., 2002): $$ s(t) = \alpha \, u(t) + [1-\alpha] \, s(t-\Delta t) \qquad{(6)}$$ where $s(t)$ is the smoothed data, $\alpha$ is the smoothing factor, and $\Delta t$ is the time step. The EMA gets its name from the fact that the weight of the contribution of each data point to the smoothed value decreases exponentially over time. This can be seen if Eq. 6 is rewritten as: $$ \dot s(t) = \tilde\alpha \, u(t) - \tilde\alpha \, s(t) \qquad{(7)}$$ defining $\tilde\alpha = \frac{\alpha}{\Delta t}$. Multiplyling by ${{\mathrm{e}^{\tilde\alpha t}}}$ and integrating yields: $$ s(t) = {{\mathrm{e}^{-\tilde\alpha t}}} \, u(0) + \tilde\alpha \int_0^t {{\mathrm{e}^{\tilde\alpha \, (t' - t)}}} \, u(t') \;\mathrm{d}t' \qquad{(8)}$$ Hence, the EMA really is a weighted average of the previous data points, with exponentially decaying weights. As it can be efficiently implemented using the recursive formula in Eq. 6, the EMA is a popular choice for smoothing data in real-time applications, such as optical mapping.

Statistical data transformation techniques can also be used to improve the quality of the data. It is common to remove the mean along each dimension in the data and rescale to unit variance. This is called whitening (Abu-Mostafa et al., 2012). For instance, in optical mapping data, the recorded intensity at points that are further away from the camera will be lower than those closer to it. After whitening each pixel by dividing by the standard deviation of its signal over time, the data will have the same variance at each point. This can also be useful for comparing data from different experiments.

To be able to compare optical mapping recordings with electrode-based EGM maps, we can calculate approximate monopolar pseudo-EGMs via a convolution: $$ u_\text{EGM}({{\bm{{x}}}}, t) \propto \int_{\heartsuit} \mathrm{d}{{\bm{{x}}}}' \; \frac{ \nabla \cdot {{\bm{{D}}}} \nabla u(t, {{\bm{{x}}}}') }{ {{\left\lVert {{\bm{{x}}}} - {{\bm{{x}}}}' \right\rVert}} } \qquad{(9)}$$ where ${{\bm{{x}}}}$ is the position of the electrode, $\heartsuit$ is the tissue domain, ${{\bm{{D}}}}$ is the diffusion matrix, and $u$ is the signal representing the transmembrane voltage. These monopolar pseudo-EGMs may be converted to bipolar EGMs by subtracting a reference EGM from each pseudo-EGM. The reference EGM can for instance be any one of the EGMs or the average of all pseudo-EGMs. For more details and additional context, see section 2.1 and chapter 2, (Kabus, Cloet, et al., 2024).

Many quantities of interest in cardiac electrophysiology can be simply obtained via thresholding and differences, such as LAT, LDT, APD, DI, and CL (section 1.1). The CV (Eq. 5) is a quantity that is highly sensitive to noise and artefacts in the data. An elegant algorithm to estimate the velocity vector from LAT maps—a scalar field $T({{\bm{{x}}}})$ in space ${{\bm{{x}}}} \in \mathbb R^{D}$—is the method by Bayly et al. (1998). The gradient $\nabla T$ of this field is the “slowness”—a vector pointing in the same direction as ${{\bm{{v}}}}$, but with the inverse value. We can then obtain the velocity vector via the relation: $$ \begin{aligned} {{\bm{{v}}}} &= \frac{\nabla T}{{{\left\lVert \nabla T \right\rVert}}^2} \end{aligned} \qquad{(10)}$$ However, as LAT increases in discrete steps such that neighbouring grid points either have the same LAT or differ by one or more steps, the gradient is not well-defined. To overcome this, the data can either be smoothed or interpolated for instance by fitting a linear function to the data in a small neighbourhood around each grid point, which is the approach by Bayly et al. (1998).

In Fig. 7, the CV is estimated from LAT and LDT maps of a pulse in the same optical voltage mapping recording of a hiAM monolayer as in Fig. 6. Linear functions—planes—are fitted at each grid point to the neighbouring LAT and LDT values. We use this to get a smooth version of the LAT and LDT maps, as well as the CV via the slope of these planes. It can be seen that in the region of interest where the figure-of-eight reentry forms, the CV of both the wave front and back is lower than in the rest of the tissue, while the APD is prolonged.

Figure 7: Estimation of CV for noisy optical mapping data for the same recording as in Fig. 6. A. Parts of three subsequent excitation waves are passing through the tissue, seen here in the optical signal $u$. B. The smoothed LAT map of pulse B5. C. The smoothed LDT map of pulse B5. D. APD of pulse B5, i.e., the difference of LDT and LAT, is prolonged in the circled region of interest. E. CV of the wave front of pulse B5 is lower in the region of interest. F. The same is true for the CV of the wave back at higher variance.

In the course of this PhD project, besides the main contributions of models of the excitation waves—the reaction-diffusion solvers Pigreads and Ithildin (Kabus, Cloet, et al., 2024) and the data-driven model creation pipeline Distephym (Kabus, De Coster, et al., 2024), to be introduced in the following sections—we have developed various companion software packages to process and analyse the data obtained from the aforementioned experiments: mainly patch clamping, optical mapping, and in-silico simulations. These packages, which contain the methods introduced in this section and more, are (1) the Python module for Ithildin (Kabus et al., 2022; Kabus, De Coster, et al., 2024; Kabus, Cloet, et al., 2024), a Python package to process and analyse excitation wave data, originally designed for data from the reaction-diffusion solver Ithildin and (2) Sappho (Kabus, De Coster, et al., 2024), another Python package to process and analyse optical mapping data. Both packages are compatible with each other. Just as the main contributions, these packages are open-source and available on GitLab.

In-silico models of cardiac electrophysiology

A common way to model the electrical activation patterns that control the mechanical contraction of the heart is the reaction-diffusion equation in the monodomain description. It arises from a number of assumptions about the nature of the electric potentials and ion concentrations in the heart muscle tissue. In this section, we will give a derivation of the monodomain equations from first principles. We will also illustrate how to numerically solve them and present typical solutions to the monodomain equations.

Bidomain description—the cell as an electrical circuit

The first assumption we usually make to describe the electrical activity in the heart’s cells is that the ion concentrations and arising potentials are continuous across the tissue, i.e., instead of looking at the microscopic structure of each cell, we instead zoom out to the mesoscopic tissue scale. The motivation for this is that the activating cells locally show similar behaviour overall—neighbouring cells usually fire together (Tung, 1978). With this assumption, we can now define the electric potentials $u_\text{i}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ on the interior of the cell continuum and $u_\text{e}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ on the exterior, in units of ${\mathrm{{m}{V}}}$ (Clayton et al., 2011; Neu & Krassowska, 1993). These potentials are also commonly referred to as the intra-cellular and extra-cellular potentials, respectively.

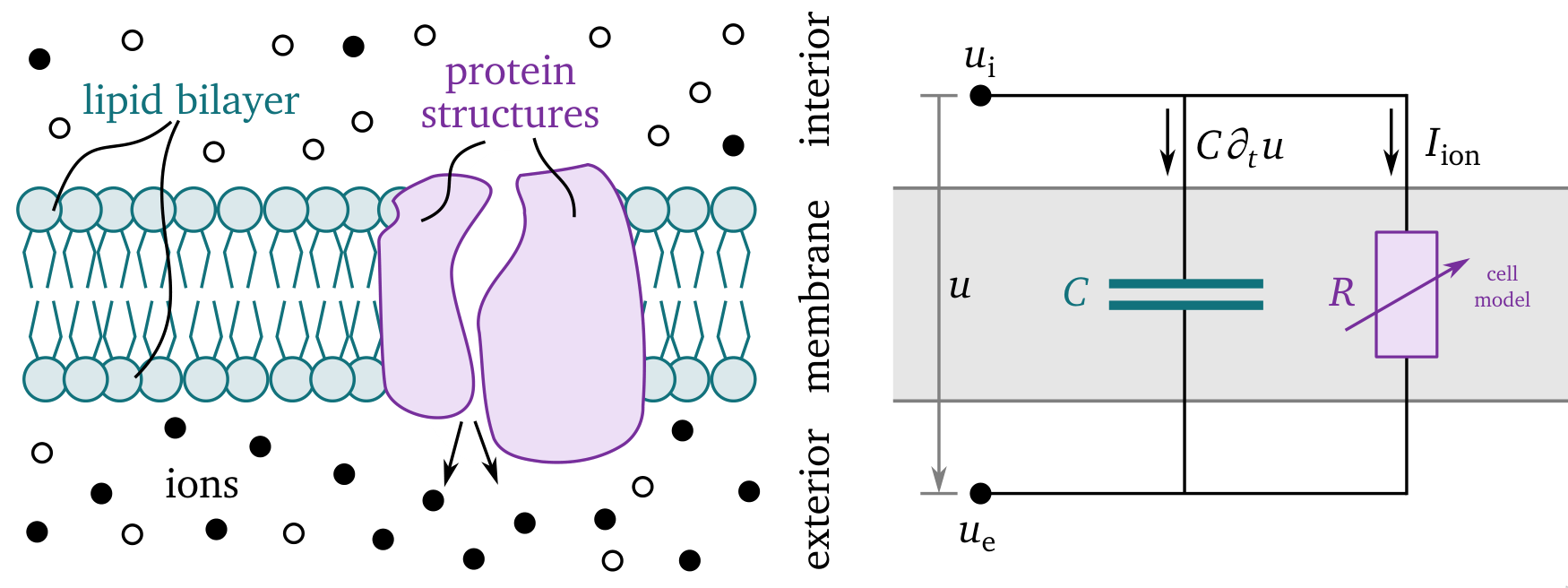

The sketch in Fig. 8 shows how the interior and exterior are separated by the cell membrane which consists of a lipid bilayer—modelled as a capacitor, and protein structures which regulate the flow of ions across the cell membrane, i.e., the total ion current $I_\text{ion}$ per unit volume in ${\mathrm{{A}{/}{m}^3}}$. The membrane has a capacitance per unit volume of $C=\beta_\text{m} C_\text{m}$ in ${\mathrm{{F}{/}{m}^3}}$, obtained from the product of the specific cell membrane capacitance $C_\text{m}$ in ${\mathrm{{F}{/}{m}{^2}}}$ and the ratio $\beta_\text{m}$ in ${\mathrm{\frac{1}{m}}}$ of the cells’ surface area to their volume (Clayton et al., 2011). The behaviour of the ion channels in the membrane is quite complex and depends not just on the potentials and ion concentrations, but also on whether or not the structures act like an open or closed “gate”, which is encoded in so-called gating variables. The collective behaviour of the ion channels is described by a cell model for cardiac electrophysiology, which was pioneered by Hodgkin & Huxley (1952) and iterated over in the following decades. In section 2.4.3 and section 2.6, we will provide more detail about a variety of different cell models. The total current across the cell membrane is $C\partial_t u + I_\text{ion}$.

Figure 8: Sketch of the main quantities in the bidomain description. On the left, a close-up view of the cell membrane is depicted which, on the right, is represented by an electical circuit. The membrane separates the cells’ interior from the exterior such that we consider different ion concentrations in each. The lipid bilayer acts like a capacitor $C$ and the protein structures control the ionic currents $I_\text{ion}$, which are here depicted as an adaptive resistor $R$. The difference between the interior and exterior potentials, $u_\text{i}$ and $u_\text{e}$ respectively, is called the transmembrane voltage $u = u_\text{i} - u_\text{e}$. The total current across the cell membrane is $C\partial_t u + I_\text{ion}$. Adapted from Hodgkin & Huxley (1952) and Alberts et al. (2002).

To each of the electric fields on the interior $-\nabla u_\text{i}$ and exterior $-\nabla u_\text{e}$ in units of ${\mathrm{{V}{/}{m}}}$, we can apply Ohm’s law to obtain the current densities $-{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} \nabla u_\text{i}$ and $-{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{e} \nabla u_\text{e}$ in units of ${\mathrm{{A}{/}{m}{^2}}}$. We denote the conductivity tensors as ${{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}$ and ${{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{e}$, for the interior and exterior respectively, in units of ${\mathrm{{S}{/}{m}}} = {\mathrm{\frac{1}{{\Omega}{/}{m}}}}$ (Clayton et al., 2011). These general conductivity tensors enable anisotropic conduction, i.e., current can spread more quickly in some directions, such as along a fibre direction versus across them. More details on the influence of this tensor on the solutions ${{\underline{{u}}}}$ will be provided in section 2.5.

As the current and charge are conserved, the total current across the cell membrane $C\partial_t u + I_\text{ion}$ takes the role of a source term for current densities on the exterior and a sink term on the interior. Therefore, for the divergence of the current densities, we obtain: $$ \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} \nabla u_\text{i} = -\nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{e} \nabla u_\text{e} = C\partial_t [u_\text{i} - u_\text{e}] + I_\text{ion} \qquad{(11)}$$ By expressing Eq. 11 in terms of the transmembrane voltage $u$ and the extra-cellular potential $u_\text{e}$, we obtain on the domain $\heartsuit\subset\mathbb R^3$ and for duration $T$ in ${\mathrm{{m}{s}}}$: $$ \begin{aligned} C\partial_t u &= \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}\nabla[u + u_\text{e}] - I_\text{ion} & \text{on}\,\heartsuit\times[0,T] & \;\;\;\text{(A)} \\ -\nabla\cdot[{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} + {{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{e}] \nabla u_\text{e} &= \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} \nabla u & \text{on}\,\heartsuit\times[0,T] & \;\;\;\text{(B)} \\ 0 &= {{\bm{{n}}}} \cdot {{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}\nabla[u + u_\text{e}] & \text{on}\,\partial\heartsuit\times[0,T] & \;\;\;\text{(C)} \\ 0 &= {{\bm{{n}}}} \cdot {{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{e}\nabla u_\text{e} & \text{on}\,\partial\heartsuit\times[0,T] & \;\;\;\text{(D)} \\ u &= u_\text{init} & \text{on}\,\heartsuit\times\{0\} & \;\;\;\text{(E)} \\ u_\text{e} &= u_\text{e,init} & \text{on}\,\heartsuit\times\{0\} & \;\;\;\text{(F)} \end{aligned} \qquad{(12)}$$ where, using the normal vector ${{\bm{{n}}}}$ on $\partial\heartsuit$, we have added the boundary condition that no currents may leave the domains, and initial conditions. This is called the bidomain continuum description of activating tissue, due to the assumption of continuous quantities across the two domains outside and inside the cells (Clayton et al., 2011). The boundary conditions for the extra-cellular potential (Eq. 12 D), can further be generalised to couple to the electrical potential around the organ, in the so-called bath (Tung, 1978).

Note that the two main variables in the bidomain equations, the transmembrane voltage $u$ and the extra-cellular potential $u_\text{e}$, are strongly coupled to each other in Eq. 12 B. Their dynamics only differ due to the discrepancy in anisotropy in ${{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}$ and ${{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{e}$.

The bidomain equations can be solved with a variety of different numerical methods (Clayton et al., 2011). For instance, a temporal step $t \rightarrow t + \Delta t$ in a naive forward Euler scheme could consist of these tasks:

Calculate the diffusion term: $$ I_\text{i} = \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}\nabla[u + u_\text{e}] \qquad{(13)}$$

Update $u$ based on Eq. 12 A: $$ u \leftarrow u + \Delta t [I_\text{i} + I_\text{ion}] \qquad{(14)}$$ respecting the no-flux boundary condition Eq. 12 C.

Calculate the diffusion term: $$ I_u = \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} \nabla u \qquad{(15)}$$

Update $u_\text{e}$ by solving the generalised Poisson equation based on Eq. 12 B: $$ \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}} \nabla u_\text{e} = -I_u \qquad{(16)}$$ with ${{\bm{{\sigma}}}} = {{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} + {{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{e}$, respecting the no-flux boundary condition Eq. 12 C.

As it is an elliptic partial differential equation, solving the Poisson equation usually involves implicit solvers which are computationally much more expensive than the solution of the reaction-diffusion equation in the first step, Eq. 12 A.

Monodomain description—a reaction-diffusion system

Another assumption can be made to get to a simpler description of the activation patterns. Assume that the anisotropy of the conduction on the interior and exterior is the same, i.e., let the conductivities be proportional to each other, ${{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{e} := \lambda {{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}$ for a dimensionless constant $\lambda > 0$ (Clayton et al., 2011). From Eq. 12, we then obtain: $$ \begin{aligned} &\nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} \nabla u = -\nabla\cdot[{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} + \lambda {{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}] \nabla u_\text{e} = -[1 + \lambda]\nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} \nabla u_\text{e} \\ \Rightarrow &C\partial_t u = \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}\nabla u + \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}\nabla u_\text{e} - I_\text{ion} = \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i}\nabla u - \frac{1}{1+\lambda} \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} \nabla u - I_\text{ion} \\ \Rightarrow &\partial_t u = \frac{1}{C} \frac{\lambda}{1+\lambda} \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} \nabla u - \frac{I_\text{ion}}{C} \end{aligned} \qquad{(17)}$$

From this, the main monodomain equation follows: $$ \partial_t u = \nabla\cdot{{\bm{{D}}}} \nabla u - \frac{I_\text{ion}}{C} \qquad{(18)}$$ where we have defined the diffusivity tensor $$ {{\bm{{D}}}} := \frac{1}{C} \frac{\lambda}{1+\lambda} {{\bm{{\sigma}}}}_\text{i} \qquad{(19)}$$

The full monodomain description can be obtained by taking the other quantities that influence the ionic currents $I_\text{ion}$ into account. These quantities describe the state of the cells, for instance via ion concentrations and gating variables. These variables are collected in the state variable vector ${{\underline{{u}}}} (t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ whose first component usually is the transmembrane voltage $u$. Let ${{\underline{{r}}}} ({{\underline{{u}}}})$ be the reaction term whose first component is $r({{\underline{{u}}}}) = - I_\text{ion}/C$ in ${\mathrm{{V}{/}{s}}}$. We can then rewrite Eq. 18 as the reaction-diffusion equation: $$ \partial_t {{\underline{{u}}}} = {{\underline{{P}}}} \nabla \cdot {{\bm{{D}}}} \nabla {{\underline{{u}}}} + {{\underline{{r}}}} ({{\underline{{u}}}}) \qquad{(20)}$$ where the unitless projection matrix ${{\underline{{P}}}}$ encodes whether a variable is to be subjected to the diffusion operator. For most cell models, only the transmembrane voltage is diffused, ${{\underline{{P}}}} = \operatorname{diag}(1, 0, ..., 0)$.

A side note on notation: We use different notation to distinguish vectors and matrices in physical space and state space. Capital letters are used for matrices, ${{\bm{{D}}}}$, ${{\underline{{P}}}}$; while lowercase letters are used for vectors, ${{\bm{{x}}}}$, ${{\underline{{u}}}}$. Boldface symbols are vectors or matrices in physical space, ${{\bm{{x}}}}$, ${{\bm{{D}}}}$; while underlined quantities are vectors or matrices with respect to the state variables, ${{\underline{{u}}}}$, ${{\underline{{P}}}}$. To illustrate this notation, Eq. 20 would read as follows in Einstein sum notation (Kabus, Cloet, et al., 2024): $$ \partial_t u_m(t,{{\bm{{x}}}}) = P_{mm'} \; \partial_{n} D_{nn'}({{\bm{{x}}}}) \; \partial_{n'} u_{m'}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}}) + r_{m}({{\underline{{u}}}};{{\bm{{x}}}}) \qquad{(21)}$$ where $m, m' \in \{1, ..., M\}$ for $M$ state variables and $n, n' \in \{1, 2, 3\}$ the spatial dimensions with $\partial_n = \partial_{x_n}$.

With no-flux boundary and initial conditions, the full monodomain description takes the form of this system of partial differential equations: $$ \begin{aligned} \partial_t {{\underline{{u}}}} &= {{\underline{{P}}}} \nabla \cdot {{\bm{{D}}}} \nabla {{\underline{{u}}}} + {{\underline{{r}}}} ({{\underline{{u}}}}) & \text{on}\,\heartsuit\times[0,T] & \;\;\;\text{(A)} \\ 0 &= {{\bm{{n}}}} \cdot \nabla {{\underline{{u}}}} & \text{on}\,\partial\heartsuit\times[0,T] & \;\;\;\text{(B)} \\ {{\underline{{u}}}} &= {{\underline{{u}}}}_\text{init} & \text{on}\,\heartsuit\times\{0\} & \;\;\;\text{(C)} \end{aligned} \qquad{(22)}$$

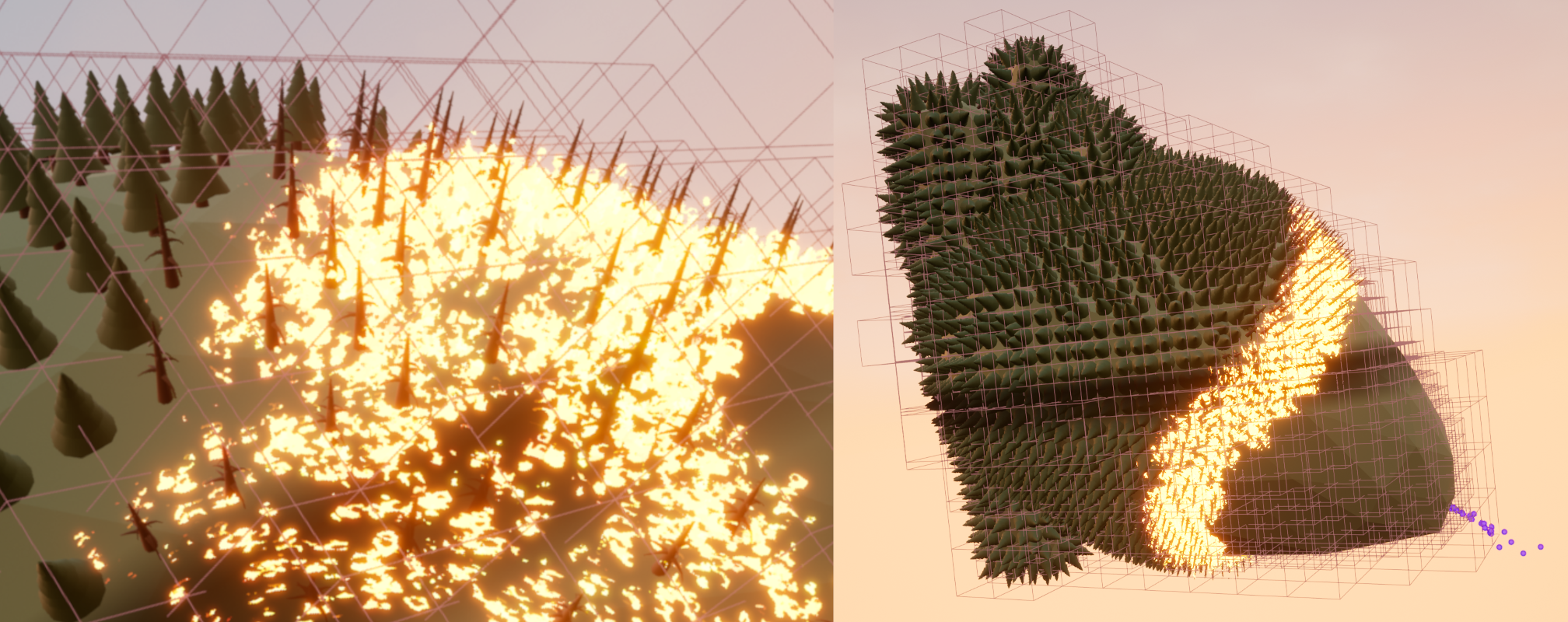

In a more general context, the monodomain equations are an example of a reaction-diffusion system, which can be used to describe a wide variety of phenomomena. All kinds of excitation waves can be modelled as reaction-diffusion systems, which, besides muscle tissue and other tissues in the body like coupled neurons (Cannon et al., 2014), includes waves in chemistry (Kapral & Showalter, 1995; Rotermund et al., 1990), or, more abstractly, the spread of epidemics (Arno et al., 2024a; Lechleiter et al., 1991). Even the propagation of a mexican wave in a sports stadium, or the spread of forest fires with subsequent recovery (Fig. 9) can be seen as excitable media.

Figure 9: Forest fires as an excitable system can also be modelled by the reaction-diffusion equations (Eq. 22). In the depicted non-scientific simulation, the spread of a forest fire is modelled on a planet in the shape of a human heart to illustrate the similarities between the two phenomena of wildfire spread and cardiac electrical excitation waves. CC-BY 2022 Judith Verdonck, Desmond Kabus et al.; Team HeartKOR at KU Leuven and Digital Arts and Entertainment at Howest.

Numerical solvers of reaction-diffusion problems

To solve the monodomain equations (Eq. 22) numerically, in contrast to the bidomain equations, one now does not need to solve Poisson’s equation. A forward Euler scheme for this is:

Calculate the diffusion term: $$ {{\underline{{d}}}} = {{\underline{{P}}}} \nabla \cdot {{\bm{{D}}}} \nabla {{\underline{{u}}}} \qquad{(23)}$$

Update ${{\underline{{u}}}}$ based on Eq. 22 A: $$ {{\underline{{u}}}} \leftarrow {{\underline{{u}}}} + \Delta t [{{\underline{{d}}}} + {{\underline{{r}}}}] \qquad{(24)}$$ respecting the no-flux boundary condition Eq. 22 B.

While this simpler numerical scheme is an advantage of the monodomain over the bidomain description, the monodomain description has the disadvantage that it is at a higher level of abstraction from the physical reality. Some level of detail necessarily gets lost during abstraction. For instance, one can not exactly recover the intra- and extra-cellular potentials, $u_\text{i}$ and $u_\text{e}$, from the transmembrane voltage $u$.

A variety of finite-differences or -elements software has been published to solve Eq. 22, some of which also have support for solving the bidomain description, Eq. 12, (Africa et al., 2023; Antonioletti et al., 2017; Arens et al., 2018; CARMEN, 2024; Cooper et al., 2020; Finsberg et al., 2023; Niederer et al., 2011; Plank et al., 2021; Rognes et al., 2017). To have control of every aspect of the numerical solution, we have also developed our own reaction-diffusion solvers. By designing every component that goes into the software ourselves, we can optimise the code perfectly for our use cases, such as including tools geared towards cardiac electrophysiology and omitting features that are irrelevant to us. Additionally, we can tweak the code to ideally match available hardware.

The first of our reaction-diffusion solvers is Ithildin (Kabus, Cloet, et al., 2024): It was written in the C++ programming language (ISO, 2023) and utilises parallelisation with OpenMPI (Graham et al., 2006), an open implementation of the message passing interface (MPI), for efficient simulations in 2D and 3D on central processing units (CPUs). It also offers a wide variety of methods for recording additional data during the simulation, such as pseudo-EGMs. Beginning with work by C. Zemlin and O. Bernus and continued development by H. Dierckx from 2009 onwards, in this PhD project, this code was polished, thoroughly improving its code in regards to the numerical methods and user-friendliness. Ithildin was published as a scientific research paper for this PhD project which is reproduced in chapter 2.

A more minimal alternative is the Python-integrated GPU-enabled reaction diffusion solver, or in short Pigreads, which we wrote to be published along with this dissertation. Instead of on CPUs, Pigreads solves the reaction-diffusion equation on graphical processing units (GPUs). While GPUs are, as the name implies, designed for calculations related to computer graphics—such as rendering 3D objects, shaders, or image processing, all of their computational power is opened up in general-purpose computing on GPUs (GPGPU). This paradigm is particularly useful for highly-parallel numerical problems, for instance, where at each of a large number of points, the same equations need to be solved independently from one another. While there are multiple solutions to utilise GPGPU capabilities, for Pigreads, we use the Open Computing Language (OpenCL) (Stone et al., 2010) to enable cross-platform GPU-parallelisation. For instance, on Nvidia GPUs, OpenCL capabilities are provided by the proprietary but highly-optimised Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) (Du et al., 2012; Nickolls et al., 2008). Similar implementations exist for other GPU architectures; there even is a CPU fallback making it possible to run Pigreads on machines without a dedicated GPU. Pigreads is designed to have as little overhead as possible, only solving the reaction-diffusion equations (Eq. 22), without any bells and whistles for maximal performance. Instead, it is relying on a simple interface with the Python programming language via Pybind11 (Jakob et al., 2017; van Rossum et al., 1995). This way, any desired custom feature can easily be implemented in a Python script with numerical and scientific Python (Harris et al., 2020; Virtanen et al., 2020) which then calls the Pigreads module.

Both of our solvers, Ithildin and Pigreads, use central finite differences to implement the spatial derivatives in Eq. 22, such as the diffusion term $\nabla \cdot {{\bm{{D}}}} \nabla u$. In the finite differences method, derivatives are approximated by calculating a weighted sum in a neighbourhood around each point on a grid—the discretisation of the domain $\heartsuit$. For instance, the one-dimensional Laplacian $\partial_x^2 u$ can be calculated as: $$ \partial^2_x u(x) \approx \frac{u(x + \Delta x) - 2 u(x) + u(x - \Delta x)}{\Delta x^2} \qquad{(25)}$$ which is an approximation that is accurate to the second order of the grid spacing $\Delta x > 0$. The weights in this case are $\frac{1}{\Delta x^2}$ for the previous and following grid point, and $\frac{-2}{\Delta x^2}$ for the grid point $x$ to calculate the Laplacian at. Note that these weights need to be adjusted if any of the neighbouring points are outside of the domain. Finite-difference weights numerically discretising the diffusion term $\nabla \cdot {{\bm{{D}}}} \nabla u$ and respecting the no-flux boundary conditions (Eq. 22) also depend on the varying value of ${{\bm{{D}}}}({{\bm{{x}}}})$ over space. The diffusion matrix ${{\bm{{D}}}}$ is usually left constant in time though, such that the weights must be calculated only once at the beginning of the numerical simulation (Clayton et al., 2011).

A final issue to address in the design of finite differences solvers of Eq. 22 using an forward Euler time stepping scheme is the Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) numerical stability criterion (Courant et al., 1928): If the time step $\Delta t$ is too large, critical details of the wave propagation in the reaction-diffusion equation might be neglegted leading to an inaccurate or even unstable solution, i.e., $u \rightarrow \infty$. The CFL condition ensures that $\Delta t$ is small enough such that the waves do not travel further than one spatial grid point during each time step. Ithildin automatically sets the time step low enough to satisfy the criterion as follows (Kabus, Cloet, et al., 2024; Li et al., 1994): $$ \Delta t < {{\left[ 2\max{({{\underline{{P}}}})} \sum_{n=1}^{N} \frac{D_{nn}}{\Delta x_n^2} \right]}}^{-1} \qquad{(26)}$$ Therefore, the maximum time step is linked to the chosen grid spacing.

Common solutions of reaction-diffusion problems

The heat equation

The two terms on the right-hand side of Eq. 22 A, encode the two mechanisms enabling the propagation of excitation waves. The diffusion term ${{\underline{{P}}}} \nabla \cdot {{\bm{{D}}}} \nabla {{\underline{{u}}}}$ spatially couples the medium and leads to the spreading of ${{\underline{{u}}}}$. Considering only the diffusion term, i.e., for the trivial model ${{\underline{{r}}}} = 0$, Eq. 22 is reduced to the heat equation: $$ \begin{aligned} \partial_t u &= \nabla \cdot {{\bm{{D}}}} \nabla u & \text{on}\,\heartsuit\times[0,T] & \;\;\;\text{(A)} \\ 0 &= {{\bm{{n}}}} \cdot \nabla u & \text{on}\,\partial\heartsuit\times[0,T] & \;\;\;\text{(B)} \\ u &= u_\text{init} & \text{on}\,\heartsuit\times\{0\} & \;\;\;\text{(C)} \end{aligned} \qquad{(27)}$$ An example of a typical solution $u(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ of the heat equation is obtained via numerical simulation using Pigreads and shown in Fig. 10: The sharp right angles of the square-shaped heat distribution $u_\text{init}(x)$ at $t=0$, gradually get smoothed out such that the temperature will eventually equalise in the entire domain for $t\to\infty$. These equations also describe how initially uneven concentrations of chemicals eventually reach a homogeneous steady-state through diffusion, which is why Eq. 27 A is sometimes also called the diffusion equation. This is also the origin of the names of the diffusion term, diffusion operator, etc.

Figure 10: A solution of the heat equation. The heat equation (Eq. 27) describes that an initially uneven distribution of heat gets diffused until a steady-state of homogeneous temperature is reached.

The model by P. Gray & Scott (1983)

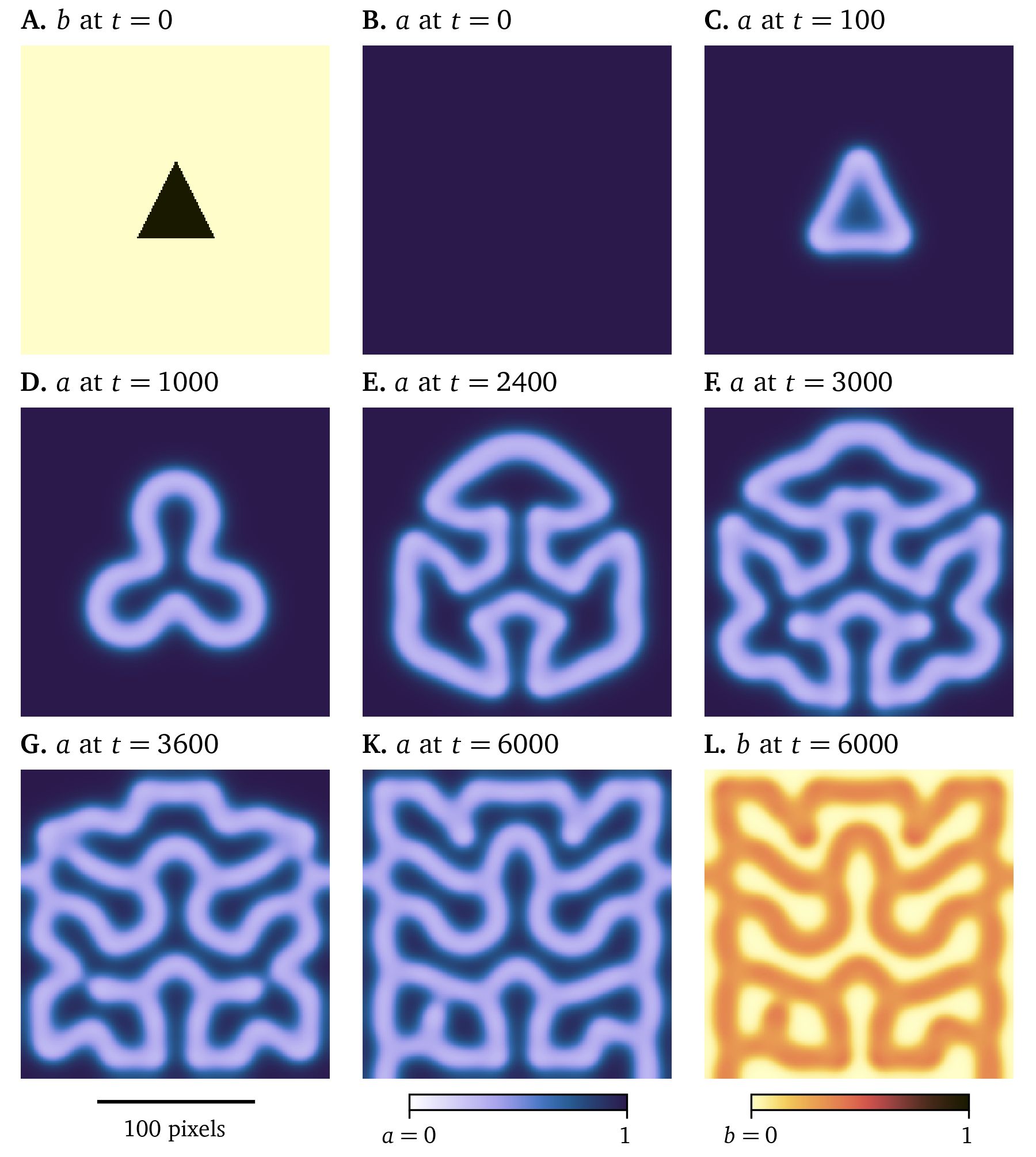

The reaction term ${{\underline{{r}}}}$ describes the local reaction at each point of the medium $\heartsuit$. Let there be two variables, ${{\underline{{u}}}} = {{{{\left[ a, b \right]}}}^\mathrm{T}}$, scaled to the interval $[0,1]$, which each describe the concentrations of one of two chemicals $A$ and $B$. One of the models by P. Gray & Scott (1983) describes the chemical reactions: $$ \begin{aligned} A + 2B &\to 3B & \;\;\;\text{(A)} \\ B &\to C & \;\;\;\text{(B)} \end{aligned} \qquad{(28)}$$ for the product $C$. Reactant $A$ is fed into the system at rate $f$, a model parameter; and the parameter $k$ determines how quickly reactant $B$ is removed. $A$ takes the role of an activator whose presence increases the reaction rate, while $B$ inhibits, i.e., slows down the reaction. The model equations then take the form: $$ \begin{aligned} \partial_t a &= D_a \nabla^2 a - a b^2 + f [1 - a] & \;\;\;\text{(A)} \\ \partial_t b &= D_b \nabla^2 b + a b^2 - [f + k] b & \;\;\;\text{(B)} \end{aligned} \qquad{(29)}$$ with diffusivities $D_a = 1$ and $D_b = 0.5$. For various parameters $k$ and $f$, the solutions of Eq. 29 are leopard-like dotted patterns or zebra-like line patterns, or even spiral waves. For example, Fig. 11 illustrates a Pigreads simulation of the model with $k = 0.062$ and $f = 0.055$ starting at a triangular initial distribution of $B$ and constant maximal concentration $a=1$ of reactant $A$. We used a grid spacing of $\Delta x = \Delta y = 1$ and a time step of $\Delta t = 0.1$ in arbitrary spatial and temporal units.

Figure 11: A solution of the model by P. Gray & Scott (1983). Starting from a simple initial condition in chemical $B$, a complex shape develops for parameters $k = 0.062$ and $f = 0.055$, cf. Eq. 29. Arbitrary units in time and space are used, the concentrations $a$ and $b$ are scaled to [0,1].

This example illustrates how the interplay of diffusion and reaction can lead to complex and chaotic behaviour: Slight variations in initial conditions can lead to vastly different outcomes.

Excitation waves in cardiac muscle tissue

Nowadays, there is a large variety of electrophysiological models that describe the excitation waves that can be found in various cells. One of the first and most influential was the model of the giant squid axon by Hodgkin & Huxley (1952), describing the neurons as an electrical circuit, as described in section 2.1, gaining them the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (Nobel Prize, 1963).

Most models fit into two categories: phenomenological and detailed ionic models. The detailed models (Courtemanche et al., 1998; Majumder et al., 2016; Paci et al., 2013; ten Tusscher & Panfilov, 2006) aim to describe as many electrophysiological processes inside each cell as possible to provide a full description of their behaviour starting on the single cell level, zooming out to the tissue level. The goal of the phenomenological models is to describe the overall wave dynamics on the tissue level while simplifying microscopic details within the cells. This reduces their computational cost, such that larger scale simulations are possible than with more detailed models. The model by FitzHugh (1961) and Nagumo et al. (1962) can be seen as a two-variable simplification of the four-variable Hodgkin & Huxley (1952) model. The model by Barkley (1991) follows similar design goals, however it was specifically designed to simulate the spiral waves arising in the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction. Other early phenomenological models specifically designed for cardiac excitation patterns are the models by Karma (1993); Aliev & Panfilov (1996), Fenton & Karma (1998), and C. Mitchell (2003). The minimal four-variable model by Bueno-Orovio et al. (2008) can be used to emulate other models, such as the ones by ten Tusscher et al. (2004) or Priebe & Beuckelmann (1998).

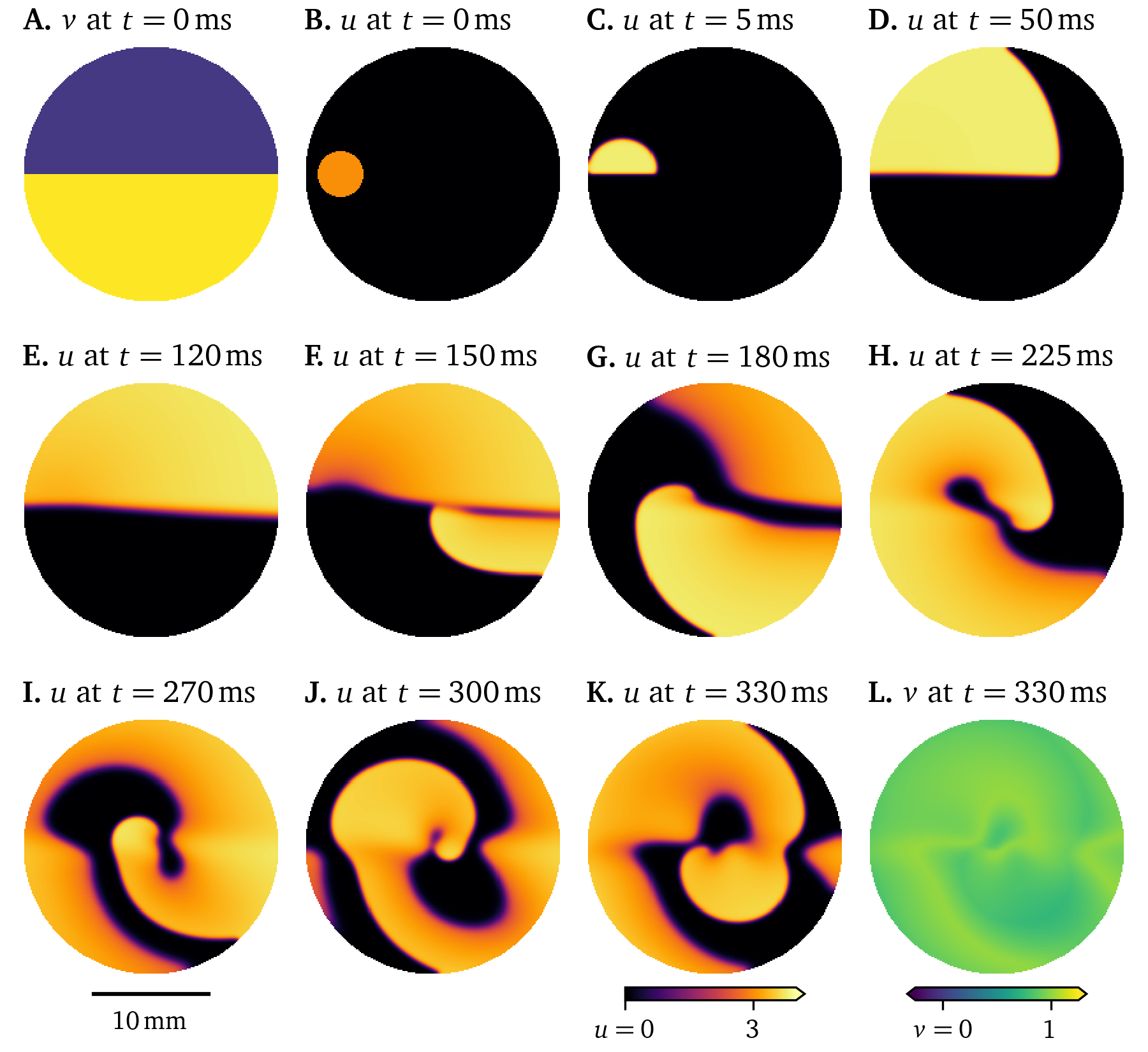

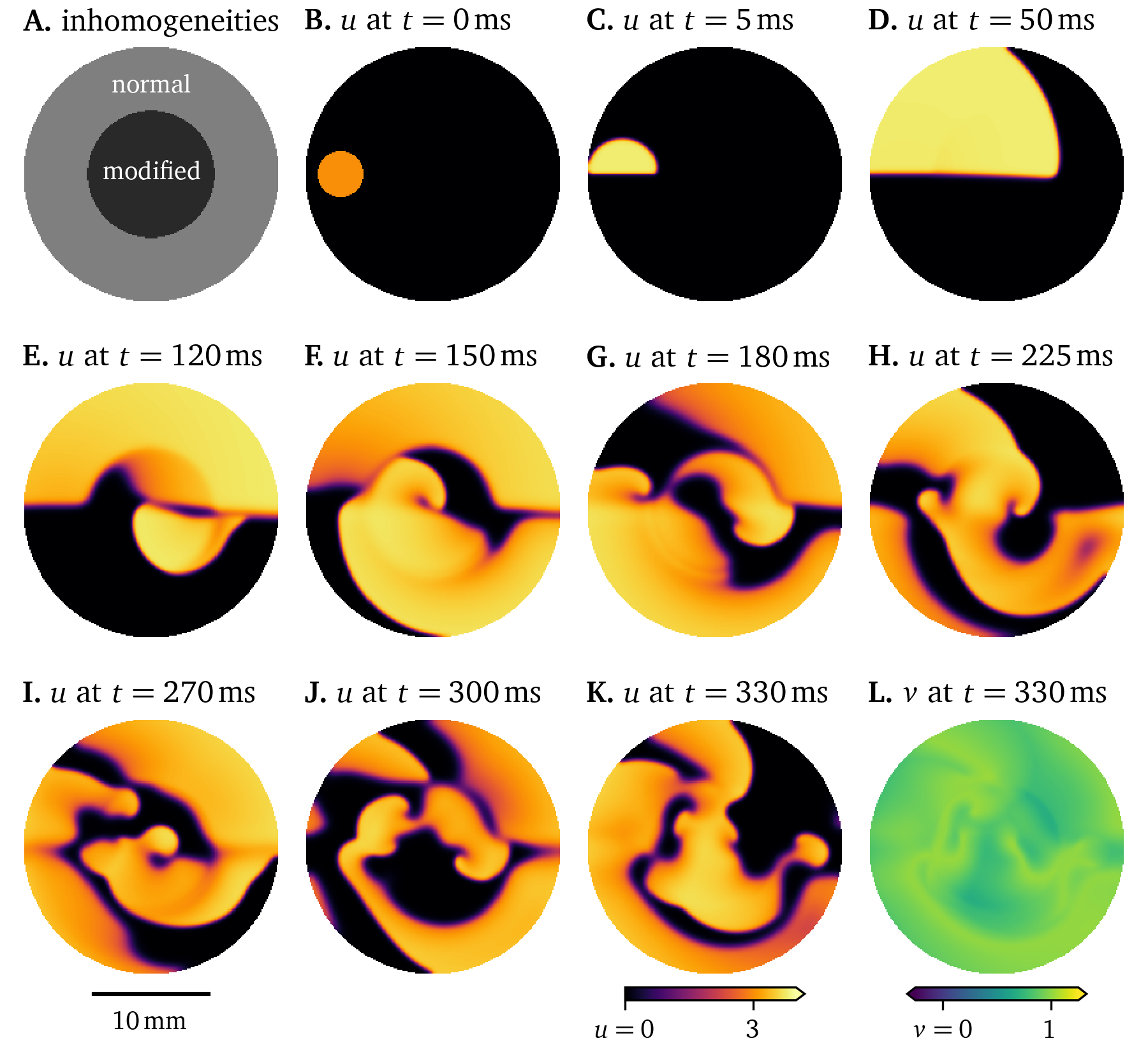

Using the smoothed version of the Karma model (Byrne et al., 2015; Karma, 1993, 1994; Marcotte & Grigoriev, 2017), we have run a Pigreads simulation on a monolayer, i.e., two-dimensional tissue, approximately in 6-well size ($R = {11~\mathrm{{m}{m}}}$) at a resolution of 200x200 pixels, with homogeneous and isotropic diffusivity $D = {0.03~\mathrm{{mm}^2{/}{m}{s}}}$, with selection matrix $P_u = 1$ and $P_v = 0.05$ for the state variables ${{\underline{{u}}}} = {{{{\left[ u, v \right]}}}^\mathrm{T}}$, using a time step of $\Delta t = 0.025$. In this simulation in Fig. 12, some of the typical electrophysiological behaviour of cardiac myocytes can be observed: The state variable $u$ which represents the transmembrane voltage in arbitrary units, smoothly switches between excited and resting state in waves of excitation that propagate through the medium. The depolarisation at the wave front, the up-stroke, occurs on a quicker time-scale than the repolarisation at the wave back. Between excitation and recovery, the transmembrane voltage stays roughly constant in the so-called plateau phase. This cycle from polarised resting state, over upstroke, plateau, and recovery, back to the resting state is called an action potential. The restitution variable $v$ describes the internal state of the cells, most crucially how recently the waves have been excited. At a high value of this variable $v$, excitation is inhibited, as can be seen at $t={0~\mathrm{{m}{s}}}$ in Fig. 12 A.

Figure 12: Simulation of the smoothed Karma model in a 6-well monolayer. Due to the initial distribution of the restitution variable, a rotor forms.

In this simulation (Fig. 12), we have chosen initial conditions such that a rotor forms: Due to the high value of $v=1$ in the lower half of the monolayer at $t={0~\mathrm{{m}{s}}}$, the initial stimulus in $u$ only triggers an action potential in the upper half, a conduction block line between the halves forms. Once the tissue recovers, it is again possible to excite the lower half. The wave turns around and follows the conduction block line creating a spiral wave rotor. These re-entrant waves have been identified as one of the mechanisms of tachycardia (R. A. Gray et al., 1995).

Influence of tissue heterogeneity and anisotropy on electrical excitation waves in the heart

An anisotropic diffusivity tensor ${{\bm{{D}}}}$, i.e., one that is not the same in every direction, encodes at which time scale diffusion—and equivalently conduction—takes place in the different directions. Cardiac muscle tissue is structured in fibres that may be further aligned in sheets. The diffusion along the fibres, encoded in diffusivity $D_{\text{f}}$, and within the sheets, $D_{\text{s}}$, is faster than in the normal direction, $D_{\text{n}}$ (Clayton et al., 2011): $$ {{\bm{{D}}}} = D_{\text{f}} {{\bm{{e}}}}_{\text{f}} {{{{\bm{{e}}}}}^\mathrm{T}}_{\text{f}} + D_{\text{s}} {{\bm{{e}}}}_{\text{s}} {{{{\bm{{e}}}}}^\mathrm{T}}_{\text{s}} + D_{\text{n}} {{\bm{{e}}}}_{\text{n}} {{{{\bm{{e}}}}}^\mathrm{T}}_{\text{n}} \qquad{(30)}$$ for the orthonormal basis vectors ${{\bm{{e}}}}_\text{f,s,n}$ along the fibres, within the sheet, and normal to the sheets, and ${{\bm{{a}}}} {{{{\bm{{b}}}}}^\mathrm{T}}$ denotes the outer product of the column vectors ${{\bm{{a}}}}$ and ${{\bm{{b}}}}$. Note that additionally the diffusivity ${{\bm{{D}}}}({{\bm{{x}}}})$ and the reaction term ${{\underline{{r}}}}({{\bm{{x}}}}; {{\underline{{u}}}})$ in Eq. 22 may depend on location, encoding spatial inhomogeneities.

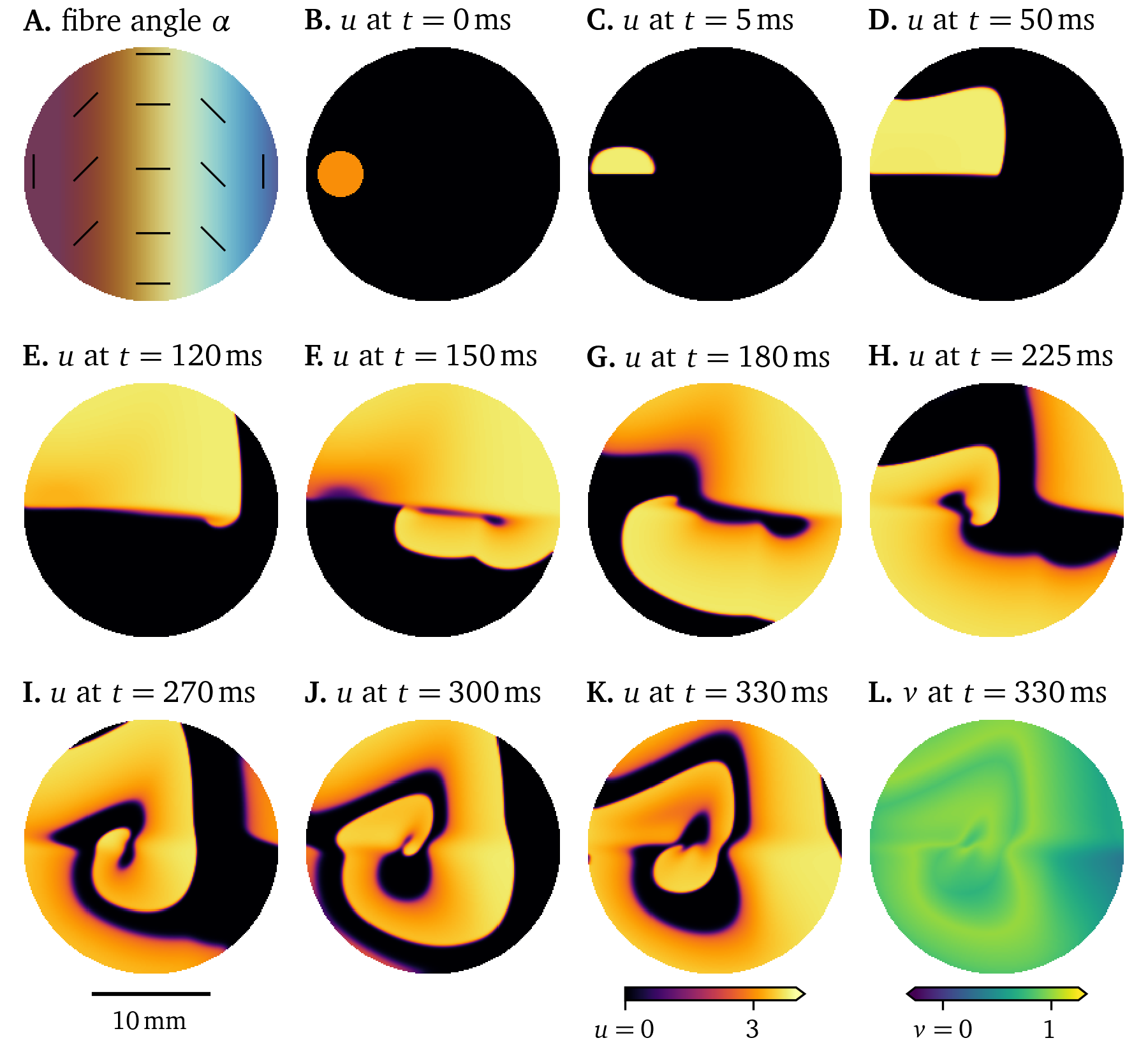

An example of the fibre direction influencing the wave propagation can be seen in another Pigreads simulation of the Karma model in Fig. 13. All parameters were left the same as in Fig. 12, except the diffusivity tensor ${{\bm{{D}}}}$: For a diffusivity along the fibres $D_{\text{f}} = {0.03~\mathrm{{mm}^2{/}{m}{s}}}$ and in the normal direction in the sheet $D_{\text{s}} = \frac{1}{5} D_{\text{f}}$, we consider fibres whose direction vary at a constant rate along the horizontal axis, as can be seen Fig. 13 A. Particularly comparing panels D of Fig. 12 and Fig. 13, it can be seen how the slower conduction normal to the fibres has changed the shape of the wave front.

Figure 13: Simulation showing the influence of fibre direction on the wave propagation in a 6-well monolayer of the Karma model.

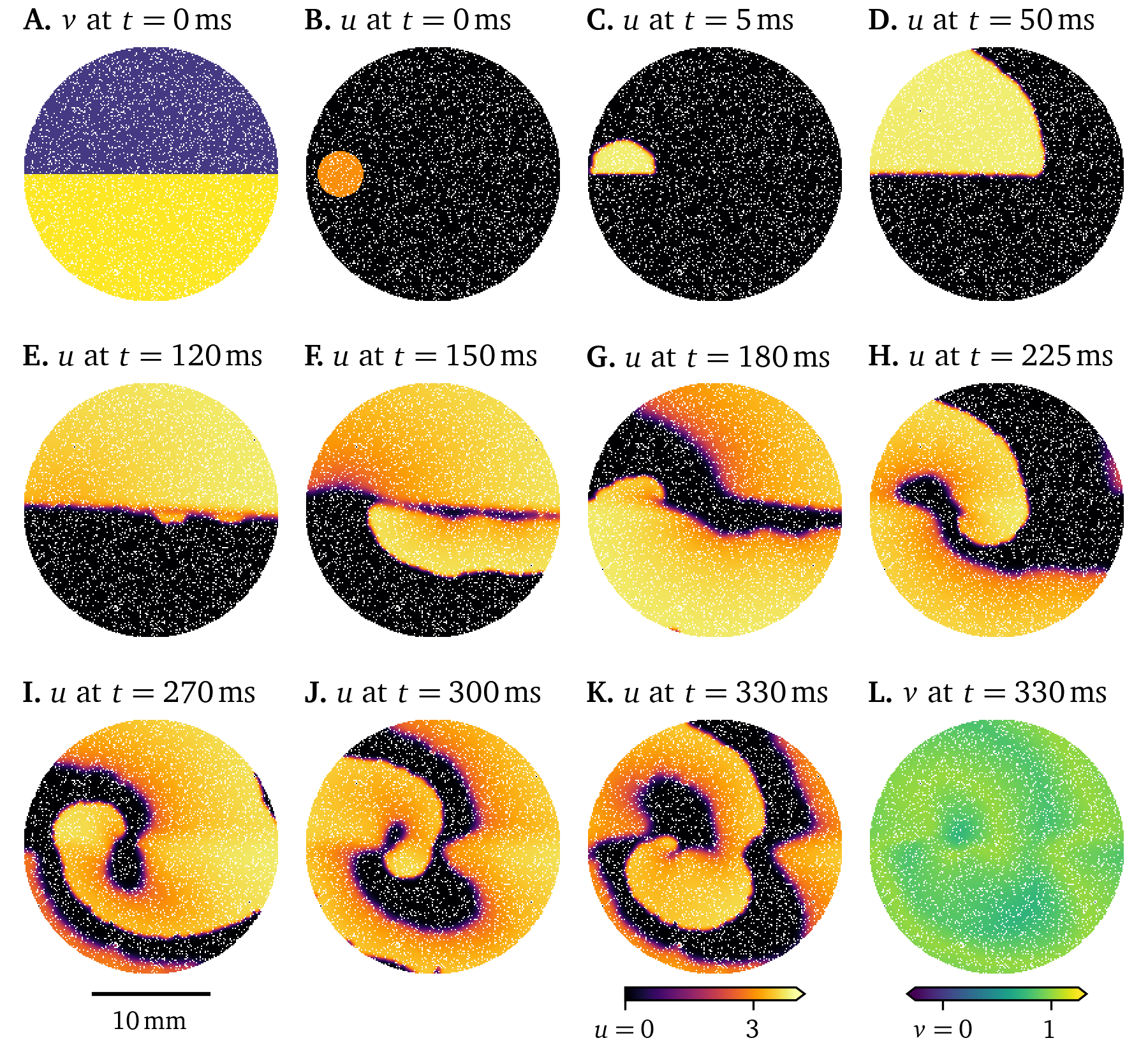

One way to numerically model fibrosis, i.e., regions of cells that can not be excited (Kazbanov et al., 2016), is to treat vertices in the finite-differences grid as exterior points. This was randomly done to of the vertices in the Pigreads simulation shown in Fig. 14. Here, the wave is slightly disturbed but still shows roughly the same behaviour as in the unmodified simulation (Fig. 12).

Figure 14: Simulation showing the effect of fibrosis on the wave propagation in a 6-well monolayer of the Karma model.

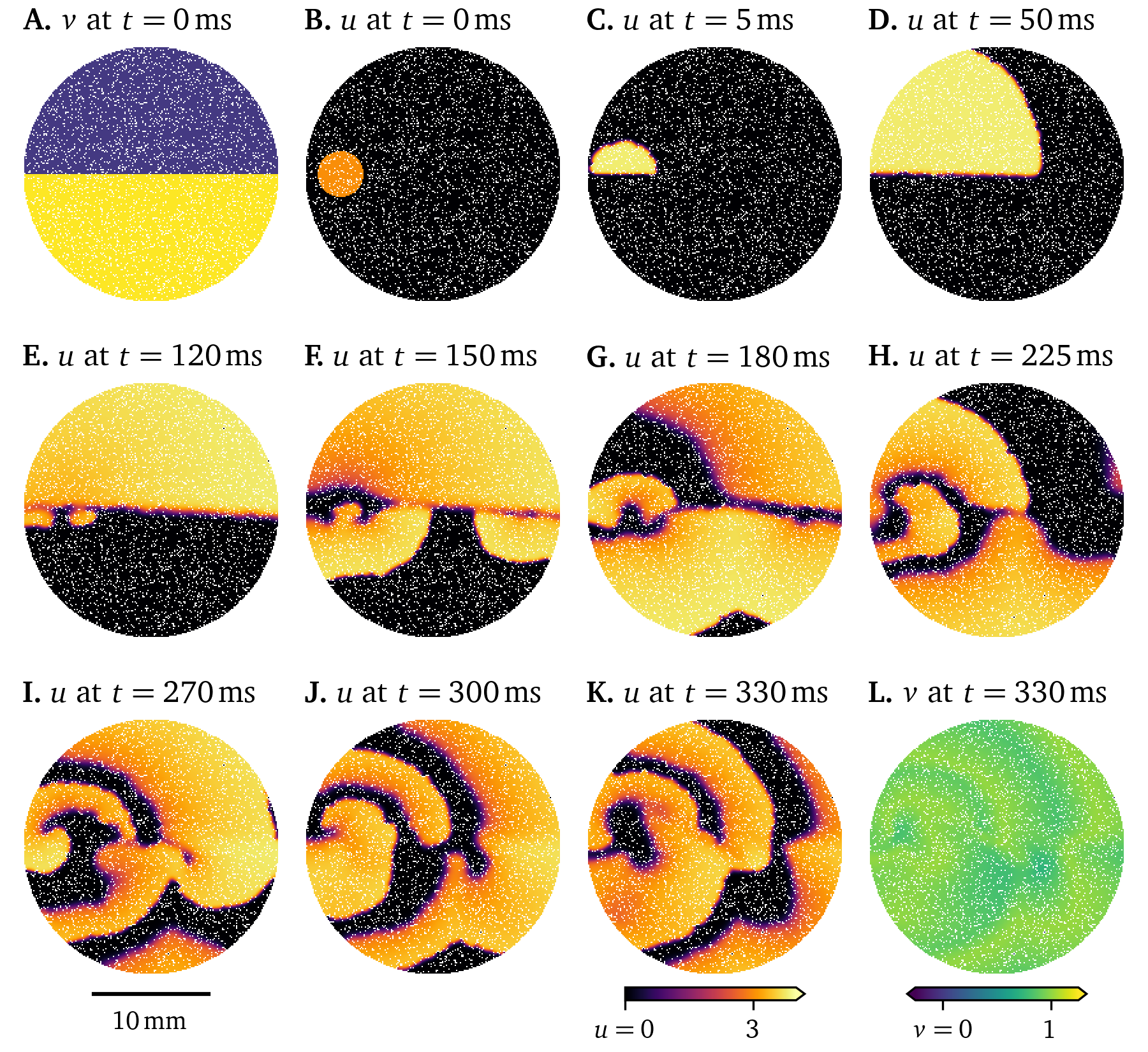

The deterministic dynamics of Eq. 22 are chaotic though, so small differences grow over time; the solutions diverge (A. Mitchell & Bruch Jr, 1985). Consider another simulation where a different subset of of vertices are modelled as fibrosis. While at first, the two solutions in Fig. 14 and Fig. 15 evolve in quite similar ways, the final frames show very different states.

Figure 15: Simulation showing chaotic behaviour in the wave propagation in a 6-well monolayer of the Karma model. Initially small differences grow until divergence from Fig. 14.

Different types of cells, the variation between cells of the same type over space, or diseased cells may be described by changing model parameters. In the Pigreads simulation in Fig. 16, we consider an inhomogeneity at the centre of the domain, where the model parameter $\epsilon$ of the Karma model as formulated in Marcotte & Grigoriev (2017) is increased by . This leads to a quicker recovery in that region, such that the rotor is sped up. This, in turn, drives the formation of more rotors across the domain. The break up of this single spiral into multiple rotors can be interpreted as a model of tachycardia evolving into fibrillation (section 1).

Figure 16: Simulation with inhomogeneous restitution parameters influencing the wave propagation in a 6-well monolayer of the Karma model.

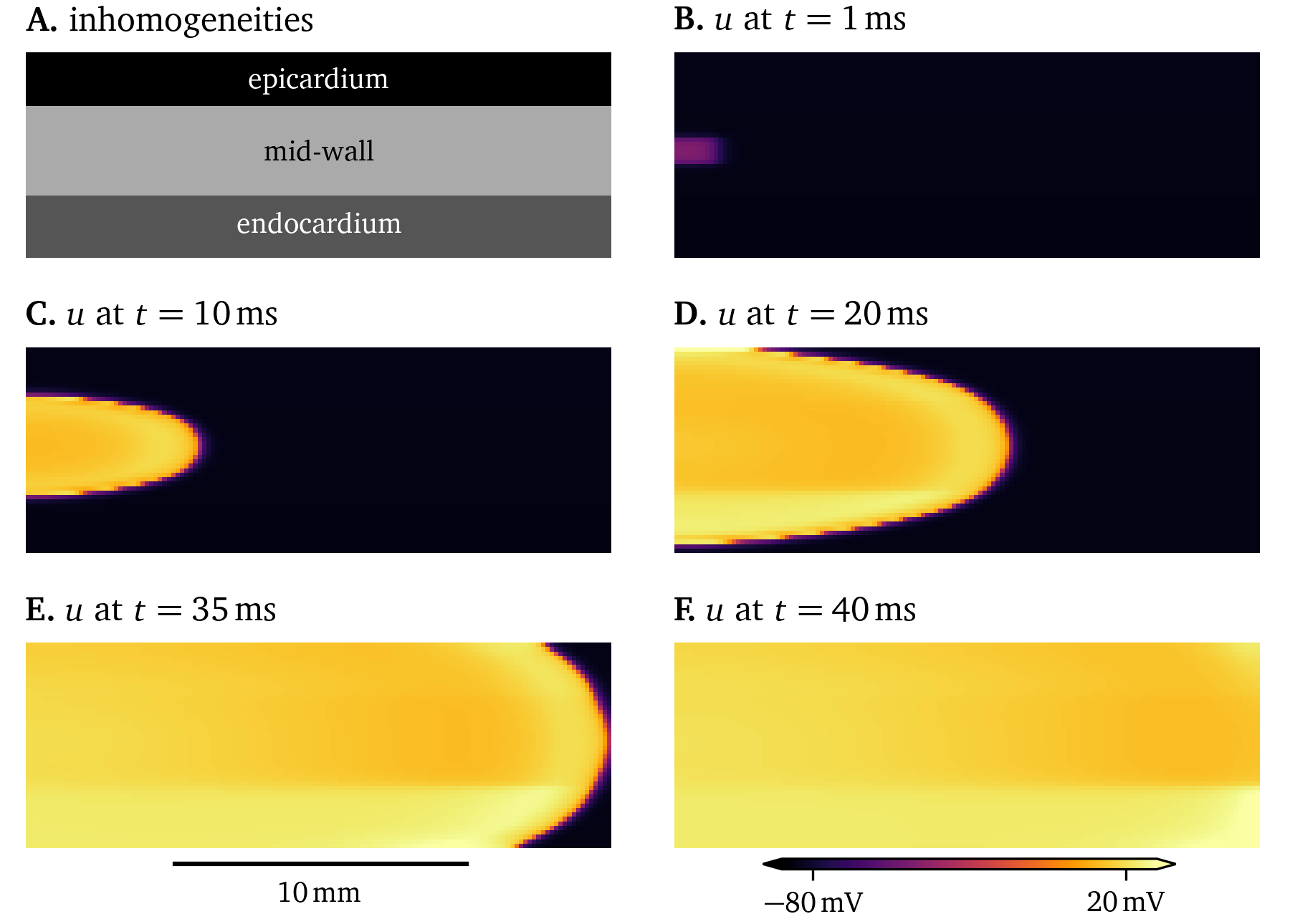

Another useful inhomogeneity is to use different, but compatible cell models for different types of cells. For instance, the model by ten Tusscher & Panfilov (2006) shows slightly different behaviour for cells in the ventricular epicardium—the outside surface of the ventricles, endocardium—the inside surface, and in the middle of the ventricular wall. A sketch-like simulation that emphasises these slight differences in the excitation along with pronounced stronger diffusion along fibres in the horizontal axis can be found in Fig. 17. Due to the differences between the epi- and endocardial variants of the model, the symmetry of the wave front is broken. Models that differ may also have numerically unstable behaviour at the interfaces between them. As these models differ only slightly, they are still compatible.

Figure 17: Simulation of a 2D domain representing a cross-section of the ventricular wall with different variants of the model by ten Tusscher & Panfilov (2006). It can be seen that the excitation is different between variants.

Detailed, ionic models of cardiac electrophysiology

Where the phenomenological models (section 2.4.3) strive for simplicity and faithfulness at the tissue level, this often comes at the cost of accuracy at the single cell level. This is in contrast to the design goals of ionic models (Courtemanche et al., 1998; Majumder et al., 2016; Paci et al., 2013; ten Tusscher & Panfilov, 2006), where it ideally includes all ionic currents and other mechanisms that effect the electrophysiological behaviour of cardiac myocytes and other excitable cells.

To create such a model, most authors adapt an existing model by optionally modifying the model equations, such that more mechanisms in the cells at hand are captured, followed by tweaking the model parameters with data from a variety of sources: Patch-clamping is usually used to record current-voltage curves that capture how a current across the cell membrane is affected by the transmembrane voltage $u$. Also obtained from patch-clamping, activation/inactivation curves can provide insight into when and how quickly the ion channel gates open in a model. Action potential duration and conduction velocity restitution curves are also used to fit such an ionic model, which may be obtained from optical mapping. Details on these methods can be found in section 1.3.

The main ion current $I_\text{ion}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ in the domain ${{\bm{{x}}}}\in\heartsuit$ over time $t\in[0,T]$ typically consists of a sum of individual currents similar to the following (Courtemanche et al., 1998; Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952): $$ I_\text{ion} = I_\text{Na} + I_\text{K} + I_\text{Ca} + ... \qquad{(31)}$$ plugging into the bi- or monodomain equations (Eq. 12 or Eq. 20). The currents $I_\star(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ are often defined as the product of scalar conductances $G_\star$, unit-less gating variables $g_{\star, a}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$, and the displacement of the transmembrane voltage $u$ from the equilibrium potentials $u_{\star}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ (Courtemanche et al., 1998; Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952): $$ I_\star = G_\star {{\left[ u - u_{\star} \right]}} \prod_a g_{\star a} \qquad{(32)}$$

The equilibrium potential $u_{\star}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ for an ion species, e.g. Na+ , K+ , Ca2+ , etc., can be calculated as (Courtemanche et al., 1998): $$ u_{\star} = \frac{R T}{Z F} \log\frac{{{\left[ \star \right]}}_\text{e}}{{{\left[ \star \right]}}_\text{i}} \qquad{(33)}$$ with the extra- and intracellular ion concentrations ${{\left[ \star \right]}}_\text{e, i}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$, the valence $Z$ of the ion, temperature $T$ in ${\mathrm{K}}$, the gas constant $R = {8.3143~\mathrm{{J}{/}{K}{/}{mol}}}$, and Faraday constant $F = {96486.7~\mathrm{{C}{/}{mol}}}$.

Ion gates $g_{\star a}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ can be modelled as (Courtemanche et al., 1998): $$ \partial_t g_{\star a} = \frac{ g_{\star a \infty} - g_{\star a} }{ \tau_{\star a} } \qquad{(34)}$$ with the steady state $g_{\star a \infty}$ and time scale $\tau_{\star a}$.

For gating variables following Eq. 34, instead of using an forward Euler scheme Eq. 24, one can use the Rush-Larssen time stepping scheme (Courtemanche et al., 1998; Rush & Larsen, 1978): $$ g_{\star a} \leftarrow g_{\star a \infty} + [ g_{\star a} - g_{\star a \infty} ] {{\mathrm{e}^{-\frac{\Delta t}{\tau_{\star a}}}}} \qquad{(35)}$$

It is common in the ionic models to, besides the transmembrane voltage $u$, have gating variables $g_{\star, a}$ and ion concentrations ${{\left[ \star \right]}}_\text{e, i}$ as state variables ${{\underline{{u}}}}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$. To keep the number of state variables as low as possible, the other quantities in Eqs. 31-34 are expressed in terms of ${{\underline{{u}}}}$.

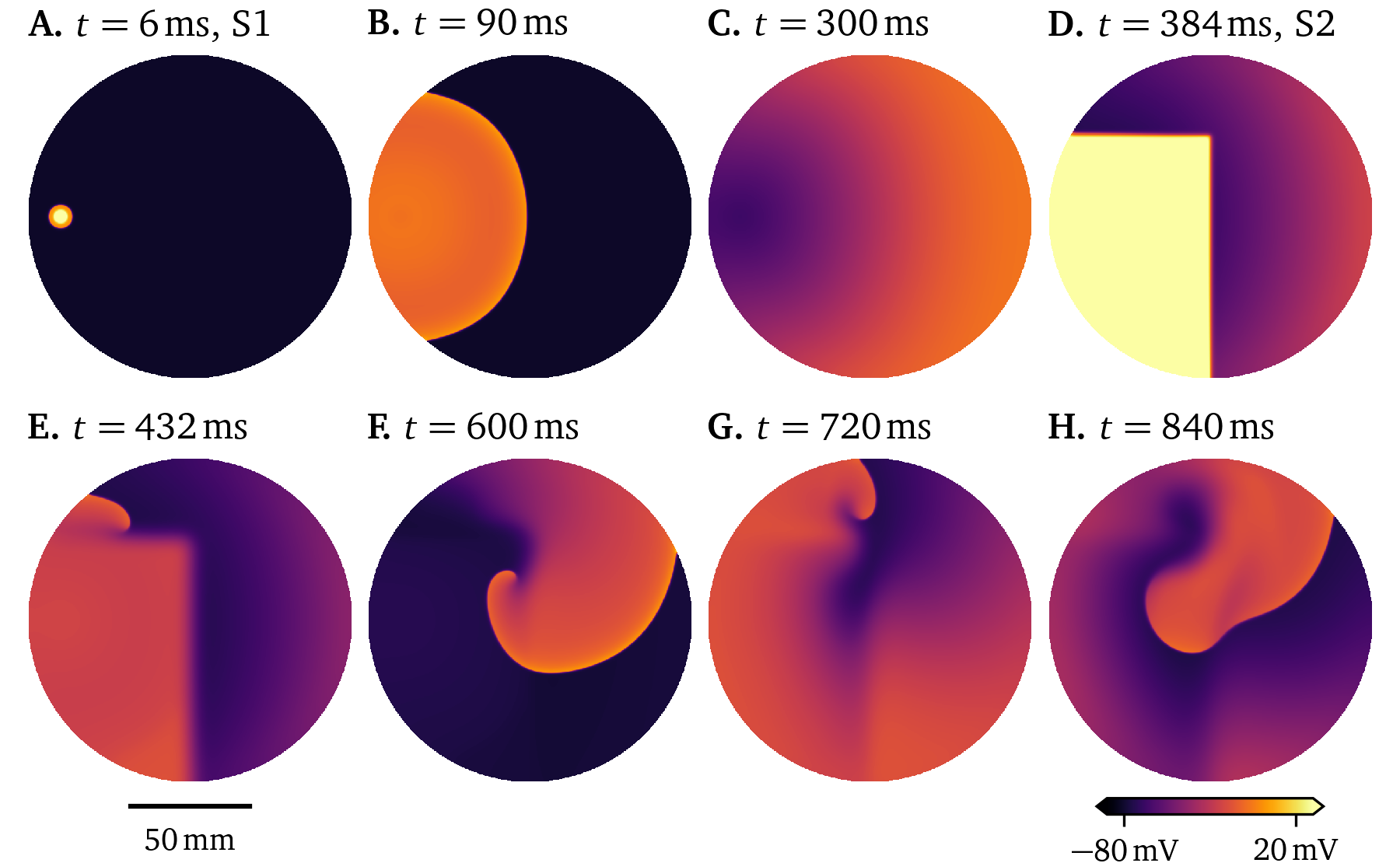

Ionic models aim to capture the behaviour of a specific type of cell or cell line. For example, the 21-variable model by Courtemanche et al. (1998) is designed for human atrial myocytes, while the 18-variable atrial model by Paci et al. (2013) describes human induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs) in an atrial-like phenotype. Tissue-level simulations for both of these are presented in Figs. 18, 19. To stimulate a rotor in these two simulations, an S1S2 protocol was used: When the wave back of an initial stimulus (S1) is sensed at a sensor location, a second stimulus is placed, such that the new excitation wave closely follows the wave back, creating a rotor. A visualisation of this protocol can also be found in Fig. 2.5. We here use current-based stimuli, essentially an additional source term on the right-hand-side of Eq. 22 A. For the simulation of the model by Paci et al. (2013) in Fig. 19, we use an additional stimulus (S0) before the protocol as, due to the restitution properties, the action potential duration of the first pulse is much longer than that of the second pulse. In the resulting wave dynamics of the two models, it can be seen how different two models for different cell lines behave even when both of them are designed as models for the same organ, in this case the atria.

Figure 18: Simulation of the model by Courtemanche et al. (1998) in a large culture dish stimulated twice following an S1S2 protocol. A meandering rotor is formed by the second stimulus at the wave back.

Figure 19: Simulation of the atrial model by Paci et al. (2013) in a 6-well culture dish stimulated three times following an S0S1S2 protocol. The well is just big enough to fit one rotor.

Limitations and alternatives

The in-silico models in the monodomain description presented in this section are powerful tools for studying the complex wave dynamics in heart muscle tissue. While here, we have shown simulations mostly on homogeneous and isotropic 2D discs to model monolayers, higher-dimensional simulations with anisotropy and heterogeneities can be performed. By choosing appropriate weights for the spatial derivatives, it is also possible to support curved surfaces like for instance the thin atrial wall (Davydov et al., 2000; Dierckx et al., 2013; Kabus, Cloet, et al., 2024).

Newer ionic models capture a lot of detail on the microscopic scale, while producing realistic electrical activation patterns on the tissue scale. Using them on the whole-organ scale, would make them a useful tool in the clinical context for personalised medicine: Procedures could be tested on a cardiac digital twin of the patient before they are actually implemented to test their efficacy and their impact on the patient. However, as the available computational power is usually still not big enough to tackle such large-scale whole-heart simulations, they are currently not feasible for patient care. This is mainly due to the resolution needed in space and time, i.e., $\Delta x$ and $\Delta t$, to accurately resolve the wave front, cf. Eq. 26. Also, the number of variables in detailed models—and hence the number of model equations, negatively impacts computational costs. With a higher number of model parameters, models also require more quite diverse and extensive measurements. Measuring every current in a cell line via patch-clamping is typically not feasible to create a full ionic model, so data from previously published models are imported that are assumed to also fit well to the cell line at hand. The variation between individual cells of a cell line is also often not taken into account. Finally, the currents are often re-balanced by scaling their conductances $G_\star$ so the action potential shape, and restitution characteristics match with observations. However, as these conventional ionic models are designed on the single-cell scale, they model single cells quite well.

One of the goals of this project was to explore alternatives or modifications to these conventional in-silico models of cardiac electrophysiology. High-resolution optical voltage mapping recordings of electrical activation patterns on the tissue scale (section 1.3.2) hold promise to enable fully-automatic, data-driven generation of electrophysiological models directly on the tissue-level. In the research paper presented in chapter 5, we explore one such method that can be used to quickly generate data-driven tissue excitation models from optical mapping data using a simple low-order polynomial model.

This method and other alternative models use machine learning techniques some of which will be presented in section 4. In section 3, we introduce methods that are useful to study the excitation patterns that can be observed in-vitro—in optical mapping data, as well as in-silico—the models that have been introduced in this section. These tools are used in the method presented in chapter 5.

Phase analysis of electrical activation patterns

Consider a model ${{\underline{{r}}}}({{\underline{{u}}}})$ in the single cell context, i.e., Eq. 22 with no spatial coupling ${{\bm{{D}}}} = 0$. Most of the models we consider in the context of cardiac electrophysiology capture both depolarisation and repolarisation—i.e., excitation and recovery. For a deterministic, continuous model function ${{\underline{{r}}}}({{\underline{{u}}}})$ to describe this behaviour, it is typically encoded in at least two variables ${{\underline{{u}}}} = {{{{\left[ u, v \right]}}}^\mathrm{T}}$. The variables of a model span the so-called state space. In state space, the model function is a vector field that describes the reaction at each possible state of the cells.

Phase analysis is a useful tool to understand the behaviour of a model by describing its state with a simple clock-like periodic variable—a so-called phase or phase angle ${\varphi}$. This section will introduce the main concepts of phase, phase singularities, phase defects, and their relation to conduction blocks. Phase defects are the main topic of two more scientific articles included in this dissertation, Kabus et al. (2022) in chapter 3 and Arno et al. (2024a) in chapter 4.

State space and phase

As an example, consider the reaction term ${{\underline{{r}}}}({{\underline{{u}}}}) = {{{{\left[ r_u, r_v \right]}}}^\mathrm{T}}$ of the simple two-variable model by Aliev & Panfilov (1996): $$ \begin{aligned} r_u &= - k u {{\left[ u - a \right]}} {{\left[ u - 1 \right]}} - u v & \;\;\;\text{(A)} \\ r_v &= - \epsilon v - \epsilon k u {{\left[ u - a - 1 \right]}} & \;\;\;\text{(B)} \\ \epsilon &= \epsilon_0 + \frac{\mu_1 v}{u + \mu_2} & \;\;\;\text{(C)} \end{aligned} \qquad{(36)}$$ with constant scalar parameters $k$, $a$, $\epsilon_0$, $\mu_1$, and $\mu_2$.

At each point ${{\underline{{u}}}} = {{{{\left[ u, v \right]}}}^\mathrm{T}}$ of the state space, this defines a unique reaction of the cells. This reaction is visualised as a vector function plot in Fig. 5.2. This figure is also coloured by the component of the reaction term in $u$-direction, $r_u$, or in the slightly different notation of that article $R_u$. For a starting state of $u=0.15$ and $v=0$, following the reaction ${{\underline{{r}}}}$ yields the trajectory ${{\underline{{u}}}}(t)$ drawn in black—the path following ${{\underline{{r}}}}$ through state space. It describes an arc around the state space, returning to the stable resting point, an attractor at $u=0$ and $v=0$. Small perturbations from this point lead to a restoring force towards the point. Diffusion and stimulus currents can be seen as additional source terms for $u$, see also Eq. 22. These offsets can raise $u$ above the critical threshold $a$ such that the system follows a similar trajectory to the aforementioned drawn one.

Therefore, under excitation, for instance from stimuli or in a spiral wave as in Fig. 12 or Fig. 2.5, the system’s state ${{\underline{{u}}}}$ evolves along a loop-like trajectory. This so-called inertial manifold (Temam, 1990) or dynamical attractor is visualised in Fig. 5.3 by colouring each point in the state space by how often it was visited in a two-dimensional monodomain simulation of the model by Aliev & Panfilov (1996). States near the dynamical extractor evolve towards and follow it (Cross & Hohenberg, 1993; Keener, 2004; Mikhailov et al., 1994). Encircled by the loop-like inertial manifold is a region—a “hole”—which contains significantly less likely states, i.e., ${{\underline{{u}}}}$ that the system in a normal excitation pattern does not evolve towards. We call this region of unlikely states the forbidden region in the state space (Arno et al., 2021).

Under repeated excitation, the system keeps evolving around in this loop in state space. So, with these cyclic trajectories in state space, it is natural to describe the system using an angle. This so-called phase describes the position on the cycle in state space. For a given state space evolution ${{\underline{{u}}}}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$ over time $t \in [0, T]$ for each point ${{\bm{{x}}}} \in \heartsuit$ in the medium, we get a function ${\varphi}(t, {{\bm{{x}}}})$. We choose ${\varphi}= 0$ as the phase at the resting state, and from there, it increases monotonously going around the loop, returning to ${\varphi}= 2\pi = 0$ (mod $2\pi$). The phase can be thought of as a “clock” for the state of the cells. A small phase value means that the system just excited, a large value closer to $2\pi$ means that the system is recovering or recovered. The details of this depend on the chosen definition of phase.

One such definition for phase is the classical phase or activation phase as an angle in state space (Bray & Wikswo, 2002; Clayton et al., 2006; R. A. Gray et al., 1998): $$ {\varphi}_\text{act} = \operatorname{arctan2}{{\left( R - R_*, V - V_* \right)}} + c \qquad{(37)}$$ where $V$ is a variable encoding the excitation of the system—typically the transmembrane voltage $u$, and $R$ is the restitution variable encoding the recovery of the system. $R_*$ and $V_*$ are constant threshold values inside the cycle’s forbidden zone, and $c$ is an offset which is typically chosen such that ${\varphi}= 0$ corresponds to the resting state.

For the definition of the restitution variable $R$, there are a few options, which all come with their advantages and disadvantages in describing the state of the system: One option is to use another state variable from ${{\underline{{u}}}}$ as the restitution variable, $R = v$. This is a common choice, particularly for two-variable models such as the models by Aliev & Panfilov (1996) or C. Mitchell (2003). If there are more than two state variables, the angle in any 2D plane in that model’s state space may be used. In Table 3.1, it can be seen that for the model by Bueno-Orovio et al. (2008), the authors choose to use the state variables $w$ and $s$ as $V$ and $R$ respectively, despite both of these variables having a less intuitive interpretation than the transmembrane voltage $u$ (Kabus et al., 2022). Another option is to extract $R$ from the temporal evolution of $V$, e.g., $R$ as a time delayed version of $V$ (R. A. Gray et al., 1995). This has the advantage to work when only a single state variable $V$ of the system can be observed. Alternatively, the Hilbert transform of $V$ may be used as $R$ (Bray & Wikswo, 2002), or the exponential moving average, see Eq. 6, (Kabus, De Coster, et al., 2024). This has the advantage to be more robust to noise.

Another way to define the phase is via the LAT, see section 1.1. The LAT at each point ${{\bm{{x}}}} \in \heartsuit$ over time $t \in [0, T]$ can be defined as the last time $t$, at which $V$ rose over a threshold $V_*$: $$ t_\text{LAT} ({{\bm{{x}}}}, t) = \operatorname{argmax}_{t' \le t} {{\left\{V ({{\bm{{x}}}}, t') = V_* \wedge \partial_t V ({{\bm{{x}}}}, t') > 0 \right\}}} \qquad{(38)}$$ LAT maps can, in the clinical context, be measured from catheter recordings in the heart (Cantwell et al., 2015), see also section 1.3.2. These maps are then used to identify conduction block lines (CBL), i.e., lines on the surface of the heart muscle that the conduction wave does not cross. CBLs are linked to arrhythmogenesis (Ciaccio et al., 2016), i.e., the formation of heart rhythm disorders, such as tachycardia and fibrillation (section 1).

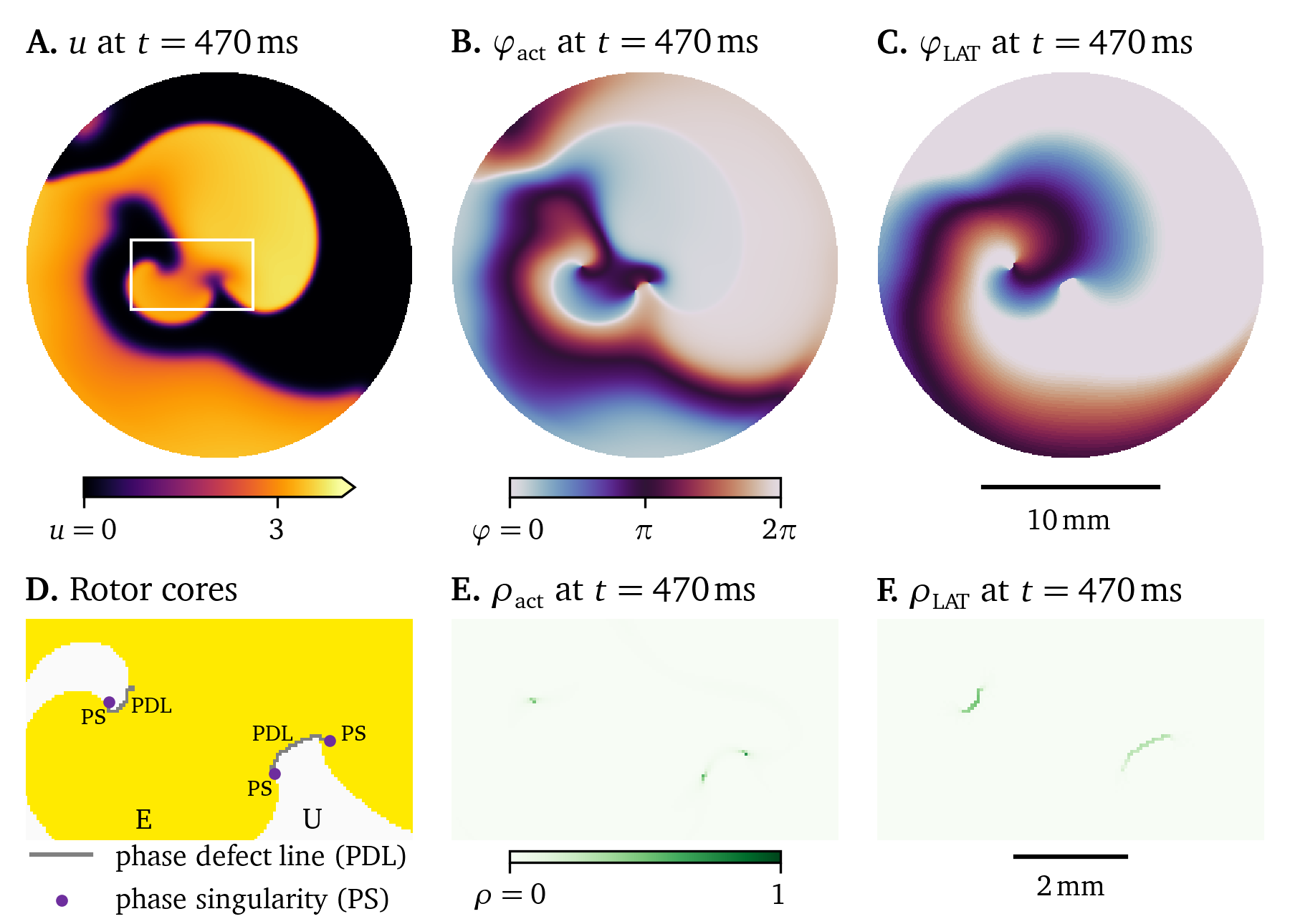

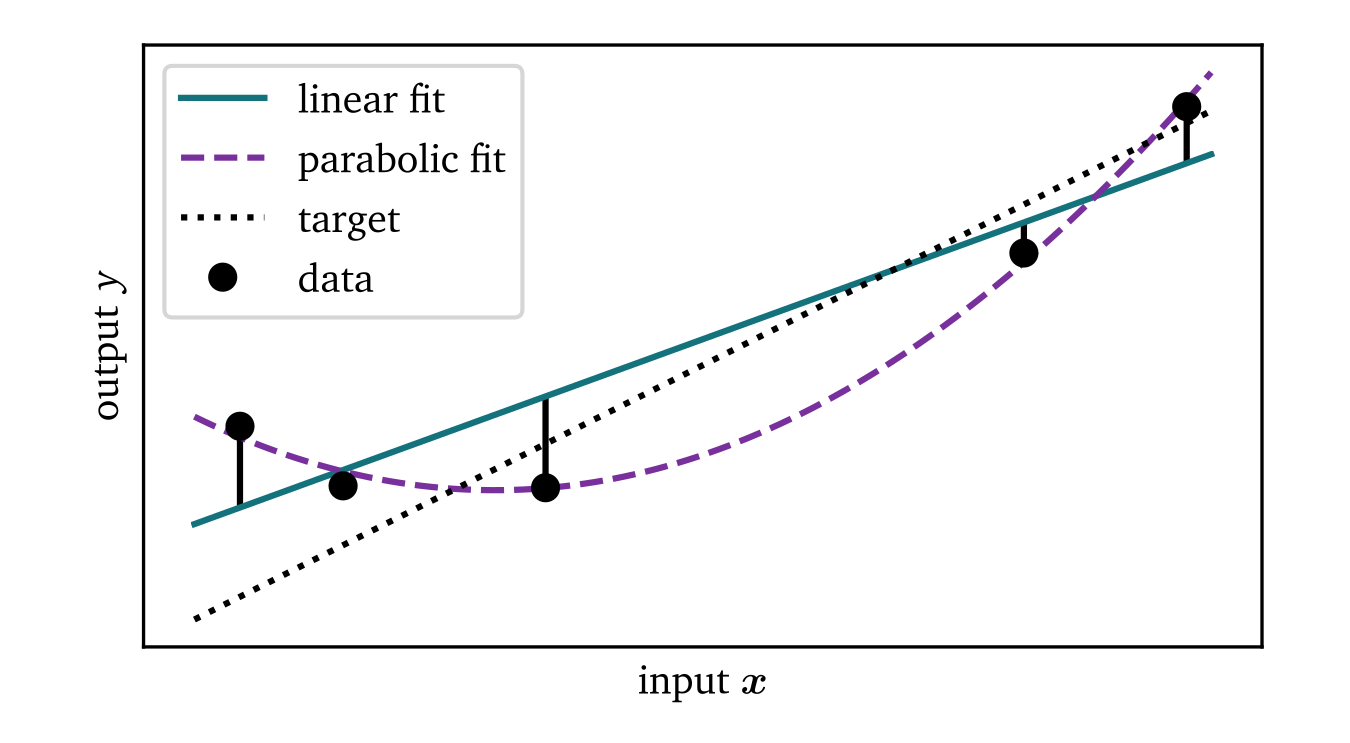

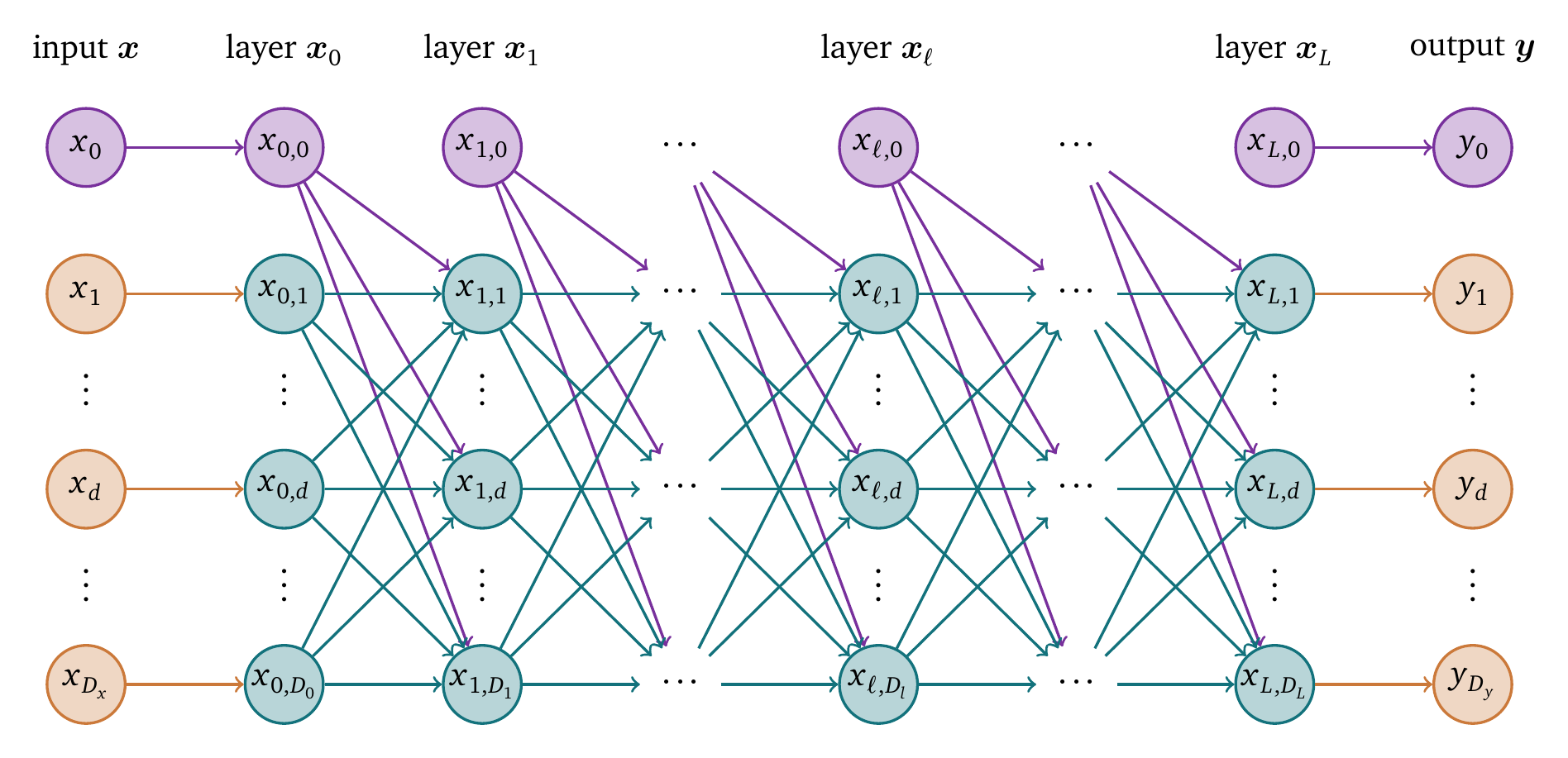

An LAT-based phase can be defined as (Arno et al., 2021): $$ {\varphi}_\text{LAT} ({{\bm{{x}}}}, t) = f(t - t_\text{LAT} ({{\bm{{x}}}}, t)) \qquad{(39)}$$ with a scaling function $f: [0,\infty) \rightarrow [0,2\pi]$, such that: $$ \begin{aligned} f(0) &= 0 \\ \lim_{\tau \to \infty} f(\tau) &= 2 \pi \\ \forall \tau: f'(\tau) &\ge 0 \end{aligned} \qquad{(40)}$$ These properties ensure that the LAT-based phase has the properties we expect from a phase to be monotonously increasing from the resting state at ${\varphi}= 0$. As the time since last excitation increases, we expect ${\varphi}$ to approach a value close to $2\pi$. For a characteristic time $\tau_0$ of recovery, choices for this scaling function $f$ are $f(\tau) = 2\pi \tanh {{\left( \frac{\tau}{\tau_0} \right)}}$ (Arno et al., 2021; Kabus et al., 2022), or $f(\tau) = \frac{2\pi\tau}{\tau_0}$, clipped to the range $[0, 2\pi]$ (Arno et al., 2024a).